Preparation is the key to success in any interview. In this post, we’ll explore crucial Historical Music Research interview questions and equip you with strategies to craft impactful answers. Whether you’re a beginner or a pro, these tips will elevate your preparation.

Questions Asked in Historical Music Research Interview

Q 1. Describe the different methodologies used in historical music research.

Historical music research employs a variety of methodologies, drawing upon both humanistic and scientific approaches. These methods are often intertwined and complementary, leading to a richer understanding of the past.

- Source Criticism: This involves meticulously examining primary sources – musical scores, letters, diaries, treatises – to verify their authenticity, date, and context. It’s like being a detective, piecing together clues to reconstruct the past.

- Ethnomusicological approaches: Studying the music of a specific culture and its social context. For example, analyzing the function of music in religious ceremonies or folk traditions.

- Musicology: This involves analyzing musical structures, styles, and forms across different periods. It’s about understanding the “grammar” of music and how it changed over time.

- Performance practice: This involves researching how music was performed in different historical periods, considering factors such as instrumentation, ornamentation, and tempo. This is a very hands-on approach that often involves performing historical music on period instruments.

- Social History: This approach explores the social and cultural context in which music was created and experienced. This might involve researching the lives of composers, the patronage system, and the social function of music in different societies.

- Digital Humanities: This is an increasingly important methodology that uses digital tools and technologies for research, analysis, and dissemination of findings. This includes things like digital libraries, text analysis of musical treatises, and using computational methods to analyse musical scores.

Q 2. Explain the significance of primary source analysis in historical music studies.

Primary source analysis is absolutely crucial in historical music studies because it provides direct evidence of past musical practices. These sources offer an unparalleled insight into composers’ intentions, the evolution of musical styles, and the social context in which music was created and received. Without primary sources, our understanding of historical music would be heavily reliant on speculation and conjecture.

For example, analyzing a composer’s surviving letters can reveal details about their compositional process, their relationships with patrons, and their thoughts on contemporary musical trends. Examining an original score, rather than a later transcription, provides information about the composer’s hand-written markings, corrections, and even the paper they used – things that can’t be discerned from later copies.

Q 3. Discuss the role of notation in understanding historical musical practices.

Notation is the key to unlocking historical musical practices. It’s not merely a system for recording sounds; it reflects the evolving aesthetic and technical understanding of music within a specific time and place. Studying historical notation involves deciphering the symbols, understanding the conventions of the time, and interpreting what the composer intended.

For instance, the evolution of notation from neumatic notation (simple melodic contours) in the Gregorian chant era to the increasingly complex and detailed systems used in the Baroque and Classical periods reflects a growing sophistication in musical thought and performance capabilities. Even subtle differences in notation – such as the use of specific ornamentation symbols or the presence of dynamic markings – can dramatically alter the interpretation of a piece.

Understanding the notation is essentially unlocking the ‘code’ that allows us to reconstruct past performances, understand the musical language of a period and even infer the instruments involved.

Q 4. Compare and contrast the musical styles of two different historical periods.

Let’s compare and contrast the musical styles of the Baroque period (roughly 1600-1750) and the Classical period (roughly 1730-1820).

- Baroque: Characterized by elaborate ornamentation, complex counterpoint, terraced dynamics (sudden shifts in volume), and basso continuo (a continuous bass line played by a keyboard instrument and cello/bassoon).

- Classical: Emphasizes clarity, balance, homophonic textures (a melody supported by chords), and a more restrained use of ornamentation. Dynamics are used more expressively and gradually.

Similarities: Both periods saw advancements in musical notation and instrumentation. Both composed works across various genres including sonatas, concertos and operas.

Differences: The Baroque was a period of exploration and extravagance in musical expression, whereas the Classical sought a greater sense of order and balance. Think of the grandeur and complexity of Bach’s music versus the elegant simplicity of Mozart’s.

Q 5. Analyze the social and cultural contexts of a specific historical musical work.

Let’s analyze the social and cultural context of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3, “Eroica.” Composed around 1803-04, it was originally dedicated to Napoleon Bonaparte, whom Beethoven admired as a champion of the revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality.

However, when Napoleon declared himself Emperor, Beethoven famously tore up the dedication, feeling betrayed by Napoleon’s abandonment of those very ideals. This act itself is a powerful reflection of the socio-political climate of the time, where revolutionary fervor was clashing with the rise of authoritarianism.

Musically, the symphony’s monumental scale and dramatic intensity reflect the revolutionary spirit and heroic aspirations of the era. The sheer size of the orchestra and the scope of the work’s emotional range mirror a society undergoing profound social and political changes. The “Eroica” is not just music; it’s a statement on the changing times. It illustrates how music could and did reflect and engage with contemporary events and ideas.

Q 6. Explain the influence of technology on the preservation and study of historical music.

Technology has revolutionized the preservation and study of historical music in several key ways.

- Digital Archiving: Digital technologies allow for the creation of high-quality digital copies of fragile manuscripts and recordings, ensuring their preservation for future generations. This overcomes issues of physical deterioration and accessibility.

- Audio Restoration: Advanced software can clean up and restore damaged audio recordings, bringing long-lost sounds to life. This allows scholars to hear and analyze historical performances with greater clarity.

- Digital Image Analysis: High-resolution scans of musical manuscripts allow researchers to zoom in on details, analyze handwriting, and identify potential forgeries. It allows for detailed analysis of the manuscript itself.

- Music Information Retrieval (MIR): MIR techniques can analyze vast quantities of musical data to identify patterns, trends, and relationships that would be impossible to detect manually.

These technological advancements have dramatically expanded access to historical musical materials and created new avenues for research. It allows us to study music in ways previously unimaginable.

Q 7. Discuss the challenges of interpreting historical musical notation.

Interpreting historical musical notation presents several challenges. The primary difficulty stems from the fact that notational practices evolved over time. What a symbol meant in one period might have a different meaning in another. Ambiguities are inherent in historical notation.

- Ambiguous symbols: Ornamentation symbols often lacked precise definitions, leaving room for multiple interpretations. For example, a trill in the Baroque period might have been performed differently by different musicians depending on musical context.

- Missing information: Earlier notation often lacked information on dynamics, tempo, and articulation, requiring researchers to make informed guesses based on other sources and their understanding of the performance practices of the time.

- Damaged scores: Many historical manuscripts are damaged or incomplete, requiring scholars to piece together fragments and make educated estimations of the missing elements.

- Cultural context: Even with clear notation, the cultural context of the music is needed to understand performance styles and musical aesthetics. For example, understanding the musical culture of a particular region or social group is essential for accurate interpretation.

Overcoming these challenges requires a deep understanding of historical notational practices, performance conventions, and the social and cultural contexts of the music. It’s a detective story of immense detail that demands patience, creativity and expertise.

Q 8. Describe your experience working with historical musical manuscripts or archives.

My experience with historical musical manuscripts and archives is extensive. I’ve spent years working in repositories like the British Library, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, and numerous smaller archives across Europe and North America. This involved not just examining scores but also understanding the context in which they were created – the physical condition of the manuscript (water damage, ink fading, etc.), the scribe’s handwriting style, and any annotations or markings added over time. For instance, I once worked with a fragmented 17th-century Italian opera score where piecing together the missing sections required detailed paleographical analysis and cross-referencing with other contemporary works. This kind of work demands meticulous attention to detail and a deep understanding of historical practices.

Beyond physical examination, I’m adept at using digital archives and online catalogs to locate and access materials. This includes navigating complex databases, using keyword searches effectively, and evaluating the reliability and authenticity of digital facsimiles. For example, I successfully located a rare set of variations on a Vivaldi concerto using a specialized database focusing on 18th-century Italian music. My ability to handle both physical and digital resources ensures a comprehensive and thorough approach to research.

Q 9. How would you approach researching the biography of a composer from the Baroque period?

Researching a Baroque composer’s biography requires a multi-pronged approach. It’s not just about finding dates and places; it’s about reconstructing their life within the socio-cultural context of the time. I’d begin by consulting standard biographical dictionaries and scholarly articles to establish a basic chronological framework. Then, I would delve into primary sources, which is where the real work begins.

- Archival Research: This would involve visiting relevant archives to search for letters, personal documents, legal records (contracts, wills, etc.), and church registers. For example, finding a composer’s baptismal record could offer crucial information about their early life and family background.

- Musical Analysis: The composer’s works themselves are vital sources. Analyzing their style, instrumentation, and dedication inscriptions can reveal biographical details or reflect their personal experiences and relationships. Consider, for example, how dedications can reveal patronage relationships.

- Secondary Sources: Contemporary accounts, travel diaries, and literary works of the period can illuminate the wider social and artistic circles in which the composer moved. Examining reviews of their performances or publications can also reveal their public image and reception.

Throughout this process, I’d be acutely aware of potential biases in the historical record and strive for a nuanced and balanced portrayal of the composer’s life.

Q 10. What are some ethical considerations in researching and presenting historical music?

Ethical considerations in researching and presenting historical music are paramount. The core principle is responsible stewardship of the source materials and respect for their cultural significance. Here are some key aspects:

- Preservation of materials: Handling manuscripts with extreme care, avoiding any practices that could cause damage. For instance, using appropriate gloves and minimizing handling when working with fragile documents.

- Accurate transcription and editing: Avoiding unnecessary intervention in original scores. Any editorial changes should be clearly documented and justified, following established scholarly practices.

- Attribution and intellectual property: Properly citing all sources and acknowledging previous scholarship. This includes respecting copyright laws where applicable.

- Cultural Sensitivity: Being mindful of the cultural context of the music and avoiding interpretations that might be insensitive or misrepresentative of the original intentions. For example, recognizing and avoiding the imposition of modern biases on interpretations.

- Access and sharing of information: Balancing the need to preserve fragile materials with the desire to make research accessible. This might involve advocating for digitalization projects while adhering to best practices for digital preservation.

Q 11. Explain your familiarity with relevant music databases and online resources.

I’m proficient in using a wide array of music databases and online resources. My go-to resources include:

- RISM (Répertoire International des Sources Musicales): An indispensable database for locating historical musical manuscripts and printed editions worldwide.

- IMSLP (Petrucci Music Library): A vast online library of public domain scores. However, I always critically evaluate the accuracy and reliability of transcriptions found on such resources.

- Various national library online catalogs: These catalogs (e.g., the Library of Congress Online Catalog, the British Library Explore) offer access to a wealth of digitized materials.

- Specialized databases: Depending on the project, I frequently utilize databases specializing in specific composers, genres, or historical periods.

I understand the limitations of online resources and always cross-reference information found online with scholarly literature and primary sources. For example, I would never rely solely on an IMSLP edition without verifying its accuracy against a reliable printed edition or manuscript.

Q 12. How would you identify and authenticate a historical musical instrument?

Identifying and authenticating a historical musical instrument is a complex process requiring expertise in several areas. It involves a combination of visual inspection, material analysis, and historical research.

- Visual Inspection: Examining the instrument’s construction, including its woods, finishes, and overall design, comparing it to known examples of the instrument type and era. Looking for maker’s marks or labels is crucial, but those can be forged.

- Material Analysis: Using techniques like dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) and x-ray fluorescence (to analyze metallic components) can provide precise dating and information on the instrument’s materials.

- Historical Research: Tracing the instrument’s provenance (ownership history) through documentation such as sales records, inventory lists, and archival photographs can establish its authenticity. Consulting relevant historical treatises and iconography can also provide valuable context.

- Expert Consultation: Consulting with experts in musical instrument making and historical musicology is essential, especially for rare or valuable instruments.

Authenticating an instrument is not a definitive process; it involves weighing the evidence and forming a reasoned judgment based on all available information. A single characteristic may not be conclusive, but the accumulation of corroborating evidence strengthens the argument for authenticity. For example, a maker’s mark might be consistent with known work from that period, but wood analysis might refine dating and reveal subtle differences in craftsmanship.

Q 13. Describe your experience with music editing software and techniques relevant to historical scores.

My experience with music editing software for historical scores is extensive. I’m proficient in using programs like Sibelius, Finale, and MuseScore, with a focus on applying editing techniques appropriate for historical scores. Simply transcribing a historical score is not enough; understanding the historical performance practices and notational conventions is crucial.

- Accurate Transcription: Transcribing the score accurately, including all the nuances of the original notation. This might involve using appropriate symbols to represent ornamentation or interpreting ambiguous passages based on context and performance practices of the era.

- Encoding Editorial Decisions: Clearly marking editorial interventions (e.g., restorations, additions, or corrections) distinct from the original notation. Using different layers or colors in the software to differentiate these is essential for transparent editing.

- Use of appropriate notation styles: Employing noteheads, clefs, and other symbols consistent with the conventions of the period. A Baroque score will require different notational considerations than a Classical one.

- Digital Imaging and Facsimile Integration: Incorporating high-quality images of the original manuscript into the digital score can help to contextualize and explain editorial decisions.

For example, when working with a score containing ornamentation that is not fully specified, I would consult treatises on performance practice and ornamentation to make informed decisions. I would also annotate those decisions thoroughly and create a clear record of my editorial choices.

Q 14. Discuss your understanding of music theory and its application in historical music analysis.

My understanding of music theory is fundamental to my work in historical music analysis. It’s not merely a set of rules; it’s a tool for understanding the underlying structure and expressive intentions of historical compositions. I utilize both traditional music theory and more specialized historical methodologies.

- Traditional Music Theory: Applying concepts of harmony, counterpoint, melody, and rhythm to analyze the structure of historical compositions. Identifying cadences, recognizing voice leading patterns, and analyzing harmonic progressions are all essential skills.

- Historical Music Theory: This incorporates a deeper understanding of the evolving conventions of music theory across different historical periods. For example, understanding the differences in modal practices between the Medieval and Baroque periods is crucial for accurate analysis.

- Analysis techniques: Employing various analytical tools such as Schenkerian analysis or Riemann’s theory of functional harmony, adapted to fit the style of the music being examined. These approaches allow for deeper insights into compositional strategies and expressive techniques.

- Contextual analysis: Understanding the historical context of the music (social, cultural, intellectual) is critical. The musical style reflects its context, and the analysis must take that into consideration.

For example, when analyzing a Bach fugue, I’d apply techniques of counterpoint analysis to identify the subject, countersubject, and episodes. Then I would examine the harmonic language, considering the particular features of Baroque harmony. This theoretical framework helps in uncovering the composer’s structural and expressive intentions.

Q 15. What are some common biases in historical music scholarship, and how can they be mitigated?

Historical music scholarship, like any historical field, is susceptible to biases. One common bias is nationalism, where scholars might overemphasize the importance of their own nation’s musical contributions while downplaying others. Another is aesthetic bias, where the scholar’s personal preferences influence their judgment of a composer’s work, potentially leading to an unfair assessment of its merit or historical significance. Survivorship bias is also a problem; we only have access to music that has survived the passage of time, which means our understanding is incomplete and might skew our perspective towards certain styles or composers that were better preserved. Finally, a presentist bias involves interpreting historical music through the lens of contemporary values and aesthetics, rather than understanding it within its own historical context.

Mitigating these biases requires a conscious and critical approach. This includes: diversifying sources by studying music from various cultures and periods, engaging with diverse scholarship to avoid echo chambers, adopting a rigorous methodology that emphasizes objectivity and transparency in analysis, and actively challenging one’s own assumptions and biases. For example, when studying 18th-century opera, one should strive to understand its original cultural context, audience reception, and performance practices, rather than simply judging its value based on modern sensibilities.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. How do you approach the interpretation of ambiguous or incomplete historical musical sources?

Interpreting ambiguous or incomplete historical musical sources requires a meticulous and multi-faceted approach. Often, we’re working with fragments of scores, damaged manuscripts, or incomplete descriptions of performances. My strategy involves building a contextual understanding of the piece by examining everything available:

- Analyzing surviving fragments: Even small pieces can reveal crucial information about the style, instrumentation, and compositional techniques.

- Comparing to similar works: Studying works by the same composer or contemporaries can help fill in missing sections or clarify ambiguities through stylistic analysis.

- Investigating historical documents: Letters, diaries, concert programs, and other written sources can provide insights into the work’s performance history, intended audience, and critical reception.

- Employing musicological principles: A deep understanding of music theory, counterpoint, harmony, and form allows for informed speculation about missing or unclear sections.

Reconstruction is always a delicate balance between informed speculation and rigorous scholarship. It is crucial to clearly document any assumptions made and to acknowledge the limitations of any reconstructions presented. For example, if a section of a baroque sonata is missing, I might use stylistic parallels from other works by the same composer to create a plausible reconstruction, clearly labeling it as such in any publication or presentation.

Q 17. Describe your experience with conducting archival research related to music.

My archival research experience spans numerous institutions, including the British Library, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, and various university archives. My work frequently involves navigating complex cataloging systems, identifying relevant materials (manuscripts, letters, librettos, performance records), and carefully examining the physical condition of documents. One particularly memorable experience involved researching a little-known composer from the early 20th century. The relevant archive was disorganized, the collection partially damaged by water, and the cataloging system notoriously inaccurate. It required weeks of painstaking searching and cross-referencing, including deciphering faded handwriting and damaged fragments, to locate crucial materials, but ultimately led to a significant discovery about the composer’s life and work.

This experience highlighted the challenges and rewards of archival research, emphasizing the importance of patience, thoroughness, and a deep understanding of the archival context.

Q 18. What methods do you employ to verify the authenticity of historical musical recordings?

Verifying the authenticity of historical musical recordings requires a multi-pronged approach. Initially, physical examination of the recording medium (e.g., 78 rpm shellac discs, acetate discs, magnetic tape) is crucial. Analyzing any accompanying documentation, including labels, accompanying notes, and provenance information can greatly assist.

Further verification involves technical analysis. This includes comparing the sound quality, recording techniques, and characteristics of the recording to those known to be consistent with the claimed date and location of recording. Consultations with audio archivists and experts in historical recording technology are often invaluable. Finally, comparison with other recordings of similar works and performers can also help establish authenticity. For instance, if a purported recording of a 1920s jazz performance shows recording characteristics inconsistent with technology of that period, it raises serious doubts about its authenticity.

Q 19. How do you ensure the accurate transcription of historical musical scores?

Accurate transcription of historical musical scores demands meticulous attention to detail and a deep understanding of historical performance practices. I begin by carefully examining the original source material, noting any ambiguities, deletions, or alterations. The process involves not just decoding the notation but also interpreting the musical context.

For example, understanding ornamentation practices of a particular period is vital in reconstructing a complete performance. I might consult treatises on performance practice from the relevant time period or compare the score to other works by the same composer to guide transcription decisions. Software tools like Sibelius or Finale can assist, but they should be used to facilitate, not replace, critical musicological judgment. The final transcription should always be accompanied by a detailed report of any editorial decisions made, including explanations for any interpretative choices. This transparency is crucial for ensuring the reliability and scholarly value of the transcription.

Q 20. Discuss your understanding of copyright and intellectual property issues related to historical music.

Copyright and intellectual property are complex and crucial considerations in historical music research. While many works from the pre-20th century are now in the public domain, the situation is nuanced. Copyright status varies by country and by the specific work. Some works might be protected under ‘moral rights’, even if the copyright has expired. The reproduction of historical musical scores or recordings, even for scholarly purposes, requires careful attention to copyright regulations and permissions.

Many archives have their own copyright policies regarding the use of their collections. Researchers need to be aware of these policies, which might restrict reproduction or publication. It is essential to thoroughly research the copyright status of any material before using it in research or publications and, when necessary, to obtain the necessary permissions from copyright holders or their representatives. Failure to do so can lead to legal issues and damage one’s scholarly reputation.

Q 21. Explain your experience with digital humanities tools for historical music research.

Digital humanities tools have revolutionized historical music research. I regularly employ tools like MusicXML for encoding and sharing musical scores in a standardized format. Digital image processing software allows for the enhancement and analysis of fragile or faded manuscripts. Transcription software, while needing careful human oversight, can assist in transcribing handwritten scores. Databases like RISM (Répertoire International des Sources Musicales) are essential for accessing information about musical sources worldwide.

Moreover, I utilize text analysis techniques to study textual sources related to music history, for example, analyzing composer correspondence for insights into their creative process. These digital tools significantly enhance the speed, accuracy, and scope of historical music research, enabling the exploration of vast datasets and facilitating collaborative research projects across geographical boundaries.

Q 22. How would you present your research findings to a non-specialist audience?

Presenting complex historical music research to a non-specialist audience requires a strategic approach that prioritizes clarity and engagement. I begin by framing the research within a broader narrative, making it relatable to their everyday experiences. For instance, instead of focusing solely on technical aspects of mensural notation, I might start by discussing the evolution of musical expression and how notational changes reflected broader societal shifts.

I use clear, concise language, avoiding jargon whenever possible. Visual aids, such as images of manuscripts, musical examples played or shown through audio-visual presentations, and even short video clips, are crucial for illustrating key points and maintaining audience interest. Think of it like telling a compelling story – you want to captivate your listeners and leave them with a lasting understanding, not bore them with technical details.

Finally, I always aim for interactive elements. A Q&A session, or even a brief hands-on activity where participants can try decoding a simple musical example, can greatly enhance understanding and make the experience more memorable. Ultimately, the goal is to inspire curiosity and appreciation for historical music, not to overwhelm with academic intricacies.

Q 23. What are some emerging trends in historical music research?

Several exciting trends are shaping historical music research. One is the increasing integration of digital humanities tools. Software for digital transcription, analysis of musical features, and the creation of interactive databases is revolutionizing how we approach sources. For example, researchers now use computational methods to identify patterns in melody, harmony, or rhythm across large datasets of music, revealing trends previously undetectable by traditional methods. This allows for large-scale comparative analyses across different styles and geographical regions.

Another significant trend is the growing focus on interdisciplinary collaboration. Historians are increasingly collaborating with musicologists, computer scientists, and even specialists in other fields like anthropology or sociology to gain a more holistic understanding of historical musical practices. For instance, the study of musical instruments is becoming increasingly reliant on scientific analysis, collaborating with material scientists to analyse wood types used in early violins.

Finally, there’s a heightened awareness of the social and cultural context of music. Research is moving beyond purely aesthetic analysis to consider the social, political, and economic forces that shaped musical production and reception. This means exploring issues of gender, race, class, and power dynamics within the historical music world, leading to a richer and more nuanced understanding of the past.

Q 24. Describe a challenging historical music research project you undertook and how you overcame the obstacles.

A particularly challenging project involved reconstructing a lost opera from the early Baroque period. Only fragmented librettos and a few scattered musical sketches survived. The primary obstacle was the sheer lack of complete material. We had to piece together the opera like a jigsaw puzzle, using a multi-pronged approach.

First, we meticulously analyzed the surviving fragments, employing techniques like comparative musicology to identify potential sources and influences. We compared melodic and harmonic patterns with works by contemporary composers to guess at missing sections. Second, we examined related archival material, including correspondence and other documents of the time period, which provided contextual clues about the production history and the composer’s intentions. Finally, we employed digital audio workstation technology to create plausible reconstructions of missing sections, based on our analysis. This involved careful consideration of Baroque compositional styles and techniques, ensuring historical authenticity while acknowledging the unavoidable gaps.

The most significant challenge was maintaining a balance between scholarly rigor and creative reconstruction. We acknowledged the speculative nature of our work, clearly documenting the evidence and the assumptions made throughout the process. The result, though incomplete, provides a plausible and historically informed interpretation of a lost masterpiece, showcasing the potential of combining traditional research methods with digital tools.

Q 25. Discuss your experience with collaborative research in historical music studies.

Collaborative research is fundamental to my work. I’ve been involved in numerous projects that have brought together scholars from diverse backgrounds and expertise. The benefits are manifold. First, it facilitates the exchange of ideas and perspectives, leading to more comprehensive and nuanced research outputs. This was clearly evident in a recent project analyzing the social impact of early music printing, which required a collaboration between musicologists, historians of the book, and social historians to build a comprehensive understanding.

Second, collaboration helps overcome the limitations of individual expertise. For instance, my expertise in historical notation systems is complemented by the digital skills of collaborators who can create interactive digital facsimiles of manuscripts, making research accessible to a wider audience. Third, collaboration helps to build a stronger sense of community and mutual support within the field. Working with others fosters intellectual debate, enhances the quality of our individual work, and encourages continuous learning and growth within the research field.

Q 26. How do you stay current with the latest scholarship in historical music research?

Staying current in historical music research requires a multi-faceted approach. I regularly subscribe to relevant academic journals, both print and online, such as the Journal of Musicology and the Music & Letters, to track newly published articles. I also attend international conferences and workshops, which provide opportunities to network with colleagues and learn about ongoing research. This direct interaction allows me to get insights on the newest research directly from the leading researchers in the field.

Furthermore, I actively participate in online scholarly communities and discussion forums, engaging with researchers across the globe and keeping abreast of new discoveries and debates. Online databases like JSTOR and Music Online provide access to a vast array of scholarly articles and primary sources, helping me stay informed about a broad spectrum of historical music research topics.

Q 27. What are your career goals related to historical music research?

My career goals center on advancing the field of historical music research and making its insights accessible to a broader audience. I aim to continue conducting rigorous and impactful research, focusing on the intersection of music history and social history. I aspire to secure a position in a leading academic institution, where I can contribute to teaching and mentoring the next generation of scholars. This includes creating engaging and informative learning materials that utilize contemporary pedagogical methods and technologies.

Beyond academia, I hope to increase public engagement with historical music. This involves collaborating with museums, libraries, and other cultural institutions to develop exhibitions and educational programs that bring historical music to life for a wider audience. Ultimately, I want my work to contribute to a greater appreciation and understanding of the rich cultural heritage represented by historical music.

Q 28. Describe your familiarity with specific historical music notation systems (e.g., mensural notation).

I possess a deep understanding of various historical music notation systems, with particular expertise in mensural notation. Mensural notation, used primarily from the 13th to the 16th centuries, represents rhythm and meter using a complex system of note shapes and symbols, differing significantly from modern notation. Understanding mensural notation involves deciphering the proportions of notes (e.g., distinguishing between a breve, a semibreve, a minim, etc.), recognizing the different modes of time signatures (perfect and imperfect), and interpreting the complexities of ligatures (groups of notes tied together).

My familiarity extends to other systems as well, including the neumatic notation of the earlier medieval period, which lacks precise rhythmic information but conveys melodic contours, and early forms of staff notation. I’m proficient in reading and transcribing music from these various systems, utilizing both traditional methods and digital tools, with the goal of accessing and interpreting musical content for study and performance.

For example, I can readily decipher a complex passage in mensural notation, identifying the rhythmic values, meter, and mode, and then translate this into a modern score. This involves both theoretical understanding of the rules of mensural notation, coupled with practical experience in interpreting the sometimes idiosyncratic handwriting and conventions of medieval and renaissance scribes.

Key Topics to Learn for Historical Music Research Interview

- Music History Methodologies: Understanding different approaches to researching historical music, including source criticism, archival research, and musicological analysis. Consider the strengths and weaknesses of each.

- Theoretical Frameworks: Applying relevant theoretical concepts (e.g., Schenkerian analysis, narratology, semiotics) to interpret historical musical scores and contexts. Practice applying these theories to specific examples.

- Genre and Style Analysis: Demonstrate a deep understanding of the evolution of musical genres and styles across different historical periods. Be prepared to discuss stylistic features and their significance.

- Social and Cultural Contexts: Analyze the relationship between music and its social, cultural, and political contexts. Consider how societal factors influenced musical creation and reception.

- Digital Humanities and Music Research: Explore the use of digital tools and technologies (e.g., digital archives, music notation software) in historical music research. Discuss practical applications and potential challenges.

- Research Presentation and Communication: Practice articulating your research findings clearly and concisely, both orally and in writing. Consider different presentation styles for academic and non-academic audiences.

- Ethical Considerations in Research: Understand and discuss the ethical implications of working with historical musical sources and archives, including copyright, access, and attribution.

Next Steps

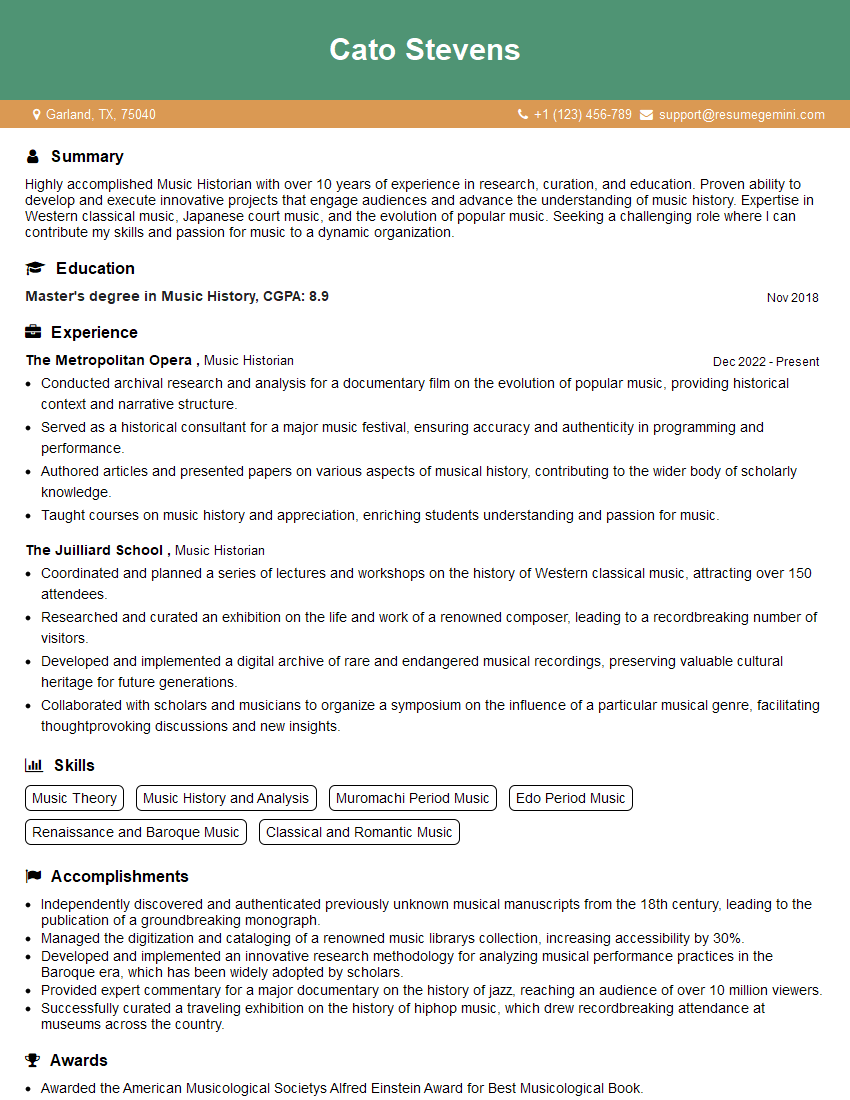

Mastering historical music research opens doors to exciting careers in academia, archives, museums, and the music industry. A strong foundation in these areas demonstrates valuable analytical, research, and communication skills highly sought after by employers. To maximize your job prospects, crafting an ATS-friendly resume is crucial. ResumeGemini can significantly enhance your resume-building experience, ensuring your skills and experience are effectively presented to potential employers. ResumeGemini provides examples of resumes tailored to Historical Music Research, offering valuable guidance in showcasing your unique qualifications.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

Hello,

We found issues with your domain’s email setup that may be sending your messages to spam or blocking them completely. InboxShield Mini shows you how to fix it in minutes — no tech skills required.

Scan your domain now for details: https://inboxshield-mini.com/

— Adam @ InboxShield Mini

Reply STOP to unsubscribe

Hi, are you owner of interviewgemini.com? What if I told you I could help you find extra time in your schedule, reconnect with leads you didn’t even realize you missed, and bring in more “I want to work with you” conversations, without increasing your ad spend or hiring a full-time employee?

All with a flexible, budget-friendly service that could easily pay for itself. Sounds good?

Would it be nice to jump on a quick 10-minute call so I can show you exactly how we make this work?

Best,

Hapei

Marketing Director

Hey, I know you’re the owner of interviewgemini.com. I’ll be quick.

Fundraising for your business is tough and time-consuming. We make it easier by guaranteeing two private investor meetings each month, for six months. No demos, no pitch events – just direct introductions to active investors matched to your startup.

If youR17;re raising, this could help you build real momentum. Want me to send more info?

Hi, I represent an SEO company that specialises in getting you AI citations and higher rankings on Google. I’d like to offer you a 100% free SEO audit for your website. Would you be interested?

Hi, I represent an SEO company that specialises in getting you AI citations and higher rankings on Google. I’d like to offer you a 100% free SEO audit for your website. Would you be interested?

good