Interviews are more than just a Q&A session—they’re a chance to prove your worth. This blog dives into essential Proficiency in Music Theory and Rhythm interview questions and expert tips to help you align your answers with what hiring managers are looking for. Start preparing to shine!

Questions Asked in Proficiency in Music Theory and Rhythm Interview

Q 1. Define meter and give examples of different time signatures.

Meter refers to the organization of beats into regular groups, creating a sense of pulse and rhythm in music. Think of it like the framework upon which a musical piece is built. Time signatures, written as two numbers stacked vertically (e.g., 4/4, 3/4, 6/8), represent the meter. The top number indicates the number of beats per measure, while the bottom number specifies the note value representing one beat.

- 4/4 (Common Time): Four beats per measure, with a quarter note receiving one beat. This is the most common time signature in Western music, often found in marches, pop songs, and many classical pieces. Think of a steady, four-beat pulse like a heartbeat.

- 3/4 (Waltz Time): Three beats per measure, with a quarter note receiving one beat. This creates the characteristic lilt of a waltz. Imagine the smooth, three-step rhythm of a waltz.

- 6/8: Six beats per measure, but grouped into two sets of three (think of two triplets). An eighth note receives one beat, creating a slightly faster and more complex rhythmic feel than 3/4. Many folk and jig-like tunes use this time signature.

- 2/4: Two beats per measure, with a quarter note receiving one beat. A simple and straightforward meter often found in marches or simpler folk songs.

Different time signatures contribute significantly to the character and feel of a musical piece. A change in time signature can dramatically alter the mood and energy.

Q 2. Explain the difference between major and minor scales.

Major and minor scales are two fundamental types of scales, differing primarily in their characteristic intervals – the distances between notes. These differences dramatically influence the emotional impact of the music.

Major Scales: Major scales are generally perceived as bright, happy, and optimistic. They are constructed using a specific pattern of intervals: whole, whole, half, whole, whole, whole, half (W-W-H-W-W-W-H, where W represents a whole step and H represents a half step). The characteristic interval is a major third between the root and the third degree.

Minor Scales: Minor scales often evoke feelings of sadness, melancholy, or introspection. There are three main types of minor scales: natural, harmonic, and melodic. The natural minor scale uses the pattern W-H-W-W-H-W-W. The harmonic minor scale alters the seventh degree to create a leading tone, adding a pull towards the tonic. The melodic minor scale ascends with a pattern of W-W-H-W-W-W-H but descends using the natural minor pattern. The characteristic interval is a minor third between the root and the third degree.

For example, the C major scale is C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C, while the C natural minor scale is C-D-Eb-F-G-Ab-Bb-C.

Q 3. What are the different types of chords and their inversions?

Chords are combinations of three or more notes played simultaneously. Their inversions alter the bass note without changing the overall chord quality. The most common types are triads and seventh chords.

- Triads: These are three-note chords built using a root, third, and fifth. They can be major (major third and minor third), minor (minor third and major third), augmented (major third and major third), or diminished (minor third and minor third).

- Seventh Chords: These add a seventh note to a triad, creating a more complex sound. They can be major seventh, minor seventh, dominant seventh, half-diminished seventh, and diminished seventh, each with a distinct character and function.

Inversions: Inversions change the order of the notes in a chord, placing different notes in the bass. The root position is when the root note is in the bass. The first inversion places the third in the bass, and the second inversion places the fifth in the bass. Inversions subtly change the chord’s voice leading and harmonic function.

For instance, a C major triad (C-E-G) in root position becomes E-G-C (first inversion) and G-C-E (second inversion). Each inversion sounds subtly different, influencing how the chord interacts with other chords.

Q 4. Describe the circle of fifths and its applications.

The circle of fifths is a visual representation of the relationships between the 12 notes of the chromatic scale. It’s arranged in a circle, where each note is a perfect fifth above the previous one. This cyclical arrangement reveals key relationships that are essential for understanding harmony and modulation.

Applications:

- Key Signatures: The circle of fifths helps visualize key signatures. Moving clockwise adds sharps, while moving counterclockwise adds flats.

- Modulation: The circle of fifths guides smooth transitions between keys, making it easier to choose related keys for modulation. Closely related keys are adjacent on the circle, making transitions smoother.

- Chord Progressions: The circle of fifths assists in crafting effective chord progressions. Common progressions often move around the circle, creating a sense of direction and resolution.

- Compositional Techniques: Understanding the circle of fifths enables composers to create pieces with a strong sense of harmonic coherence and direction.

For a composer, the circle of fifths acts as a roadmap for key relationships, facilitating informed harmonic decisions and creating well-structured pieces.

Q 5. How do you identify and analyze rhythmic patterns?

Analyzing rhythmic patterns involves identifying the durations of notes and rests, and understanding how they are grouped and organized within a measure. This is crucial for understanding the rhythmic pulse and the overall groove of the music.

Steps for identifying and analyzing rhythmic patterns:

- Notate the rhythm: Write down the rhythmic notation of the passage, paying close attention to note and rest durations.

- Identify the time signature: Determine the time signature to understand how beats are grouped.

- Divide into beats and measures: Divide the rhythm into beats based on the time signature and then into measures.

- Look for patterns: Identify recurring rhythmic motifs or phrases. These can be simple or complex.

- Analyze the subdivisions: Examine how beats are further subdivided into smaller rhythmic units (e.g., triplets, dotted notes).

- Analyze rhythmic relationships: Determine the relationships between different rhythmic elements, such as syncopation or rests.

For example, a simple rhythmic pattern might be a repeated sequence of quarter notes and eighth notes. A more complex pattern could involve syncopation or unusual groupings of notes.

By meticulously analyzing rhythmic notations, you can effectively understand the complexity and character of the rhythmic structure.

Q 6. Explain the concept of syncopation and its use in music.

Syncopation is the deliberate placement of accents on weak beats or off-beats, creating a rhythmic surprise or unexpected emphasis. It contrasts with the established rhythmic pattern, adding rhythmic interest and a sense of rhythmic excitement.

Use in Music: Syncopation is widely used across many musical genres, adding a sense of rhythmic drive and energy. It’s particularly prevalent in jazz, funk, afrobeat, and many forms of popular music. For example, the rhythmic feel of a swing tune often relies heavily on syncopation, which makes it “swing.” In classical music, composers like Stravinsky frequently employed syncopation to create a sense of rhythmic unease or dynamism.

In simple terms, if the expected strong beat is played without emphasis and a weak beat is played with emphasis, it constitutes syncopation.

Q 7. What is modulation, and how is it achieved?

Modulation is the process of changing from one key to another within a musical piece. It’s a fundamental compositional technique that creates harmonic variety, adds emotional depth, and provides a sense of progression and development.

How it’s achieved: Modulation is achieved by gradually transitioning the harmony from the original key to the new key. This typically involves:

- Using common chords: Sharing chords between the two keys helps smooth the transition.

- Chromaticism: Using notes outside the original key can create a bridge to the new key.

- Pivot chords: These chords belong to both the original and the new key, providing a pivot point for the modulation.

- Sequence: Repeating a musical phrase in a different key helps the ear acclimate to the new key.

Effective modulation requires careful planning, ensuring the transition sounds natural and avoids jarring leaps in tonality. Successful modulation can significantly enhance a piece’s narrative and dramatic impact.

Q 8. Describe different types of melodic intervals.

Melodic intervals describe the distance between two notes. They’re classified by both their size (number of half steps) and their quality (major, minor, perfect, augmented, diminished). Think of it like measuring the distance between two points on a ruler, but instead of inches, we use musical steps.

- Perfect Intervals: These include perfect unison (same note), perfect octave (12 half steps), perfect fifth (7 half steps), and perfect fourth (5 half steps). They have a very strong, consonant sound.

- Major Intervals: Major second (2 half steps), major third (4 half steps), major sixth (9 half steps), major seventh (11 half steps). Major intervals sound bright and relatively stable.

- Minor Intervals: Minor second (1 half step), minor third (3 half steps), minor sixth (8 half steps), minor seventh (10 half steps). Minor intervals have a more somber or slightly dissonant quality.

- Augmented Intervals: These are a half step larger than a major or perfect interval. For example, an augmented fourth (6 half steps) is a half step larger than a perfect fourth.

- Diminished Intervals: These are a half step smaller than a minor or perfect interval. A diminished fifth (6 half steps) is a half step smaller than a perfect fifth.

Understanding interval quality is crucial for composing and analyzing melodies. For example, a major scale is defined by its characteristic intervals: major seconds and major thirds between consecutive notes.

Q 9. Explain the function of counterpoint in music.

Counterpoint is the art of combining independent melodic lines simultaneously. Imagine two or more people having a conversation – each voice has its own distinct melody, but they work together to create a richer, more complex musical texture. The function of counterpoint is to add depth, interest, and complexity to music.

Effective counterpoint requires careful consideration of:

- Voice Leading: Smooth and logical movement of individual melodic lines to avoid awkward leaps or clashes.

- Harmony: The simultaneous sounding of notes creates chords; counterpoint needs to consider the harmonic implications of the independent melodies.

- Rhythm and Texture: The rhythmic interplay between voices can enhance the overall musical effect. The texture can range from homophonic (one main melody with accompaniment) to polyphonic (multiple independent melodies).

Different styles of counterpoint (e.g., strict counterpoint, free counterpoint) exist, each with its own set of rules and conventions. Composers like Bach mastered the art of counterpoint, creating intricate and beautiful musical works.

Q 10. What are the characteristics of different musical forms (e.g., sonata form, rondo)?

Musical forms provide a blueprint for organizing musical ideas. They act like the architectural plans of a building, giving structure and coherence to the overall piece. Here are characteristics of two common forms:

- Sonata Form: Typically found in instrumental music, sonata form has three main sections: Exposition (presents two contrasting themes), Development (explores those themes in new ways often with more dissonance), Recapitulation (restates the themes, usually in the tonic key). Think of it as a story with an introduction, a climax, and a resolution. Beethoven’s symphonies are prime examples.

- Rondo Form: This form features a recurring main theme (A) interspersed with contrasting themes (B, C, etc.). The formula often looks like A-B-A-C-A-B-A or variations thereof. It’s memorable due to the repeated A section. Think of it like a song with a catchy chorus.

Other common forms include binary form (two sections, A-B), ternary form (three sections, A-B-A), theme and variations, and fugue (a complex polyphonic form based on a single subject).

Q 11. How do you analyze a piece of music in terms of form and harmony?

Analyzing a piece of music for form and harmony involves a multi-step process.

- Identify the overall form: Does it seem to follow sonata form, rondo, theme and variations, or another established structure? Look for recurring themes and sections.

- Outline the sections: Divide the piece into distinct sections based on thematic material and changes in key or dynamics. Create a formal outline (e.g., A-B-A for ternary form).

- Analyze the harmony: Determine the key, identify chord progressions, and note any modulations (changes of key). Pay attention to cadences (harmonic resolutions) and their function.

- Connect form and harmony: How does the harmonic language support the form? Do changes in harmony coincide with transitions between sections? For example, does a dominant chord lead to a tonic chord at the end of a section?

- Consider melodic and rhythmic elements: These are essential parts of the musical expression. Analyze how melodies unfold within the form and how rhythmic patterns contribute to the overall effect.

By systematically examining these aspects, you can develop a comprehensive understanding of how form and harmony work together to create a unified and meaningful musical experience.

Q 12. Explain the difference between harmony and counterpoint.

While both harmony and counterpoint deal with the simultaneous sounding of notes, they differ in their focus.

- Harmony focuses on the vertical aspect of music—the relationships between simultaneously sounding chords and notes. It’s concerned with the overall harmonic progression and the function of chords within a key. Think of it as looking at the music from a bird’s-eye view, seeing the overall chord structure.

- Counterpoint focuses on the horizontal aspect—the independent melodic lines that weave together. It’s concerned with the melodic interactions between the voices and the voice leading between notes. This is like looking at the music from a side view, seeing the independent melodic lines.

A piece of music can incorporate both harmony and counterpoint. For instance, a Baroque fugue might feature multiple independent melodies (counterpoint) that simultaneously create rich harmonic progressions (harmony).

Q 13. Describe different types of cadences.

Cadences are points of harmonic arrival or rest in a musical phrase. They signify the end of a phrase or section and create a sense of closure. Different types of cadences have varying degrees of finality.

- Perfect Authentic Cadence: This is the strongest and most conclusive cadence. It consists of a dominant chord (V) resolving to a tonic chord (I). It’s often the ending of a musical piece.

- Imperfect Authentic Cadence: Similar to a perfect authentic cadence, but the dominant chord is not in root position.

- Plagal Cadence (Amen Cadence): This cadence moves from subdominant (IV) to tonic (I). It often has a more peaceful and less conclusive feel than an authentic cadence.

- Deceptive Cadence: Instead of resolving to the expected tonic chord, the dominant chord resolves to a chord other than the tonic, usually the vi chord. This creates a sense of surprise or suspension.

- Half Cadence: Ends on a dominant chord (V), leaving a sense of incompleteness. It often occurs in the middle of a phrase.

Recognizing different types of cadences is vital for analyzing musical structure and understanding a composer’s expressive intentions.

Q 14. What is a figured bass, and how is it used?

A figured bass is a shorthand notation system used in Baroque music and earlier periods. It consists of a bass line with numbers and symbols placed above or below it, indicating the chords to be played above the bass line. The numbers represent the intervals above the bass note.

For example:

6 5This figured bass notation indicates a first inversion C major chord (C-E-G) above the bass note C, because 6 represents an interval of a sixth (E above C) and 5 represents an interval of a fifth (G above C). Other symbols indicate things like chords, suspensions, and ornaments. The realization (fully spelling out the chords from the figured bass) is left to the performer or arranger, allowing for some improvisation and creativity.

Figured bass was a crucial tool for realizing harmonies in an era before complete chord notation was standardized. It provided a framework for improvisation and allowed composers to convey complex harmonic ideas concisely.

Q 15. Explain the concept of tonality and atonality.

Tonality and atonality are fundamental concepts in music describing the presence or absence of a tonal center, or home note. Tonality refers to music that centers around a specific key, creating a sense of harmonic stability and direction. Think of it like a journey with a clear destination – the tonic (the ‘home’ note). The music gravitates towards this tonic, creating a feeling of resolution and completeness. Most Western classical music, folk music, and many popular genres are tonal.

Atonality, on the other hand, is the absence of a tonal center. There’s no single note that feels like ‘home,’ and the music explores a broader range of harmonies without a sense of resolution or direction. Think of it like wandering aimlessly without a map. It’s a characteristic of much 20th-century music, particularly the work of composers like Arnold Schoenberg.

Example: A simple tonal piece might consistently use the notes of C major, constantly returning to C as a resting point. An atonal piece would utilize a more random selection of notes, with no sense of hierarchical importance to any single pitch.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. What is a leading tone, and what is its function?

The leading tone is the seventh degree of the diatonic scale (the major or minor scale). Its function is to create a powerful pull toward the tonic (the first degree of the scale). It’s a semitone below the tonic, creating strong harmonic tension that demands resolution.

Think of it like a spring that’s been compressed; it’s yearning to release its energy. The leading tone’s inherent instability creates a sense of anticipation that’s musically satisfying when resolved to the tonic. In the key of C major, B is the leading tone, creating a strong drive towards the tonic C.

Example: In a C major chord progression, if you have a G major chord followed by a C major chord, the B note in the G major chord acts as the leading tone, pulling irresistibly to the C in the following chord. This creates a sense of movement and resolution.

Q 17. Describe the different types of musical textures.

Musical texture describes the relationship between different melodic and harmonic lines in a piece of music. There are several main types:

- Monophony: A single melodic line without accompaniment. Think of a solo singer or a single instrument playing a melody. It’s the simplest texture.

- Homophony: A melody with harmonic accompaniment. This is the most common texture in Western music, like a song with a melody and chords played on a piano or guitar.

- Polyphony: Two or more independent melodic lines occurring simultaneously. Think of a fugue or a round, where multiple voices or instruments sing or play different, yet interwoven melodies. It’s complex and often creates a rich and layered sound.

- Heterophony: Simultaneous variations of the same melody. Think of a folk music tradition where several instruments play the same tune, but with slight embellishments or variations.

The texture can change throughout a piece, adding to its expressive range.

Q 18. How do you notate rhythmic complexities?

Notating rhythmic complexities involves using a variety of symbols and techniques to accurately represent the timing and duration of notes. Standard notation uses note values (whole, half, quarter, eighth, sixteenth, etc.), rests, and beaming to represent basic rhythms. However, more complex rhythms often require additional symbols and techniques:

- Tuplets: These indicate groups of notes played in a different time value than the prevailing meter. For example, a triplet indicates three notes played in the space of two. It’s written with a small ‘3’ above or below the notes.

- Syncopation: This involves placing accents on weak beats or off-beats, creating a rhythmic surprise. It is notated by placing notes strategically across the bar.

- Dotted Notes: A dot after a note increases its duration by half its original value. A dotted half note is equal to a half note plus a quarter note.

- Tie: Used to connect two notes of the same pitch, creating a single, longer note.

Example: A triplet of eighth notes would be notated as (3) above or below three eighth notes beamed together.

Q 19. What are some common rhythmic notation symbols?

Common rhythmic notation symbols include:

- Note heads: Represent the pitch and duration of a note.

- Stems: Lines extending from note heads.

- Beams: Connect multiple notes of the same value.

- Flags: Small lines attached to the end of stems.

- Dots: Increase the duration of a note by half its value.

- Rests: Symbols representing silence.

- Tuplet brackets: Enclose notes played as tuplets.

- Time signature: Indicates the meter.

Q 20. How would you teach a student to understand complex time signatures?

Teaching complex time signatures effectively requires a multi-faceted approach. I’d start with breaking down the time signature into its constituent parts: the upper number (numerator) indicates the number of beats per measure, and the lower number (denominator) indicates the type of note that receives one beat.

For example, 7/8 means there are seven eighth notes per measure. I would then use a combination of methods:

- Clapping and Counting: Encourage students to clap and count the beats to internalize the rhythm.

- Visual Aids: Use diagrams or charts to represent the beats visually.

- Simple Exercises: Start with simpler rhythmic patterns within the complex time signature, gradually increasing complexity.

- Real-world Examples: Show how the time signature is used in different musical pieces, highlighting its effect on the groove and feel.

- Listening Exercises: Have students listen to music in the given time signature to develop their aural understanding.

By combining these techniques, a student can develop a comprehensive understanding of even complex time signatures.

Q 21. How do you identify and correct rhythmic errors in a score?

Identifying and correcting rhythmic errors in a score requires careful listening and analysis. I would employ the following steps:

- Careful Listening: Play the score and listen attentively for any rhythmic discrepancies. Often, even slight rhythmic inconsistencies can disrupt the overall flow.

- Visual Inspection: Examine the score visually, checking for any notation errors like misplaced notes, incorrect note values, or missing rests.

- Metrical Analysis: Analyze the rhythmic patterns against the established meter. Look for accents that don’t fit the meter or unexpected rests disrupting the flow.

- Comparison with Other Scores: If possible, compare the score with recordings or other printed versions to cross-reference the rhythmic patterns.

- Collaboration: If working on a score collaboratively, discuss the identified errors with colleagues to achieve consensus on the correct rhythmic interpretation.

Once the errors are identified, the corrections would be made meticulously, ensuring that all rhythmic values are correctly notated, and the overall flow of the piece remains consistent and musically effective.

Q 22. Explain the concept of rhythmic displacement.

Rhythmic displacement, simply put, is the shifting of rhythmic accents or note values away from their expected position within a metrical framework. Imagine a regular heartbeat – that’s your meter. Displacement is like adding an unexpected extra strong beat, or delaying a beat you’d anticipate. It creates surprise and rhythmic interest.

For example, consider a simple 4/4 time signature. A typical strong beat falls on beats 1 and 3. Displacement might involve placing a strong accent on beat 2 or 4, or syncopating a note by placing it on an off-beat, creating a rhythmic pull or drive.

In a musical context, this is often achieved through techniques like syncopation (accents on off-beats), hemiola (superimposing a triple meter over a duple meter), or using complex rhythmic patterns that subtly shift the perceived downbeat.

Q 23. How does rhythmic phrasing contribute to musical expression?

Rhythmic phrasing is crucial for musical expression because it dictates how we ‘breathe’ and group notes to create meaning and emotional impact. Just as a speaker uses pauses and phrasing to deliver a speech effectively, a musician uses rhythmic phrasing to shape a melody or a harmony.

Think of it like building sentences in a language. Words themselves are musical notes, but how they are grouped into phrases determines their meaning and impact. A well-crafted rhythmic phrase creates tension and release, building anticipation and delivering emotional climaxes. Short, staccato phrases can convey excitement or urgency, while long, legato phrases can express serenity or sadness.

Consider the difference between a simple march and a bluesy ballad. The march features regular, repetitive rhythmic phrases emphasizing the downbeats, while the ballad may feature more nuanced phrasing with rubato (flexible tempo) and rhythmic variations that emphasize the emotional depth of the music.

Q 24. How do you analyze the rhythmic structure of a piece of music?

Analyzing the rhythmic structure of a piece of music involves a multi-step process. First, I determine the time signature, which gives the basic pulse and metrical framework. Next, I identify the main rhythmic patterns and motifs. This involves noting the duration of each note and rest, and their arrangement within a measure.

I then look for patterns of accentuation: where are the strong beats emphasized? Are there any syncopations? Does the rhythm use simple or complex meters? I analyze the relationship between different rhythmic layers, such as the interplay between melody, harmony, and accompaniment. Do these rhythmic layers move independently or interlock?

Finally, I consider how rhythmic phrasing shapes the musical narrative. How are the rhythmic ideas grouped into phrases? How do these phrases build tension and release? Software like Sibelius or Finale can be helpful in visualizing and quantifying these rhythmic elements, and identifying patterns that might not be immediately apparent.

Q 25. Describe different rhythmic patterns across various musical genres.

Rhythmic patterns vary widely across genres, reflecting the cultural and historical context of the music. For example, West African music often employs complex polyrhythms, where multiple rhythmic layers interact simultaneously, creating a rich and intricate texture. These polyrhythms are often based on interlocking patterns of different durations.

In contrast, many forms of Western classical music may utilize more regular and predictable rhythmic patterns. However, even within classical music, there’s enormous diversity. Baroque music might feature elaborate ornamentation and rhythmic variations within a steady metrical framework, while Romantic music might embrace more rubato and flexible phrasing.

Jazz features syncopation as a core element, creating a sense of swing and groove. Rock music often employs driving, repetitive rhythms, while electronic music often utilizes synthesized rhythms that are highly precise and quantized.

Q 26. Explain how rhythmic variation can create musical interest.

Rhythmic variation is essential for creating musical interest because it prevents monotony and keeps the listener engaged. A constant, unchanging rhythm can quickly become tedious. Variation can be introduced in many ways: changing the note values, introducing syncopation, altering the meter, or employing different rhythmic motifs.

Imagine listening to a piece of music with only quarter notes throughout. It would be very monotonous. However, introducing eighth notes, dotted notes, rests, or changing the rhythmic pattern after a few bars can drastically enhance the piece’s appeal and create points of both anticipation and surprise. It’s the contrast between expected and unexpected that sustains the listener’s interest. Think of it as analogous to using different sentence structures and lengths in written language to make your writing more engaging.

Q 27. How do you use rhythmic analysis to inform your performance?

Rhythmic analysis is fundamental to informed performance. Understanding the underlying rhythmic structure allows me to accurately convey the composer’s intentions and bring the music to life. By identifying the rhythmic patterns, accents, and phrasing, I can shape my playing to create the appropriate emotional effect.

For instance, if I identify a series of syncopations in a jazz piece, I’ll emphasize those off-beats to create the characteristic swing feel. Similarly, if the music features a gradual increase in rhythmic complexity, I might adjust my tempo and articulation to reflect this evolution. Understanding the interplay of rhythmic layers allows for balanced and nuanced playing, ensuring that no rhythmic part is overpowering or overshadowed.

Q 28. How can you effectively communicate rhythmic ideas to others?

Effectively communicating rhythmic ideas involves using a combination of verbal and non-verbal techniques. Clearly explaining the time signature and metrical framework is crucial. I often use hand gestures to demonstrate rhythmic patterns, and clapping or tapping my foot to illustrate the pulse and subdivisions.

When working with others, I might use rhythmic notation software or create simple graphic representations of the rhythmic patterns. It’s always helpful to provide concrete examples, such as playing or singing short rhythmic phrases to demonstrate the desired feel. Instructing others to count aloud together can assist in establishing a common understanding of the beat and rhythm. Furthermore, utilizing aural examples from recordings of the style you’re teaching can greatly assist.

Key Topics to Learn for Proficiency in Music Theory and Rhythm Interview

- Melodic Construction: Understanding intervallic relationships, melodic contour, and phrase structure. Practical application: Analyzing existing melodies and composing your own, demonstrating understanding of melodic tension and release.

- Harmonic Analysis: Identifying chord progressions, analyzing voice leading, and understanding functional harmony. Practical application: Analyzing scores from various musical periods, demonstrating comprehension of harmonic function and relationships.

- Rhythmic Complexity: Mastering syncopation, polyrhythms, and complex meter changes. Practical application: Notating and performing complex rhythmic patterns accurately and with rhythmic precision.

- Form and Structure: Understanding different musical forms (e.g., sonata form, rondo, theme and variations) and their structural elements. Practical application: Analyzing the formal structure of musical works and applying this knowledge to composition.

- Counterpoint: Understanding the principles of writing independent melodic lines that work together harmoniously. Practical application: Creating two-part or three-part inventions demonstrating skillful voice leading and contrapuntal techniques.

- Ear Training: Developing the ability to accurately identify intervals, chords, and rhythms by ear. Practical application: Sight-singing, dictation exercises, and aural analysis of musical excerpts.

Next Steps

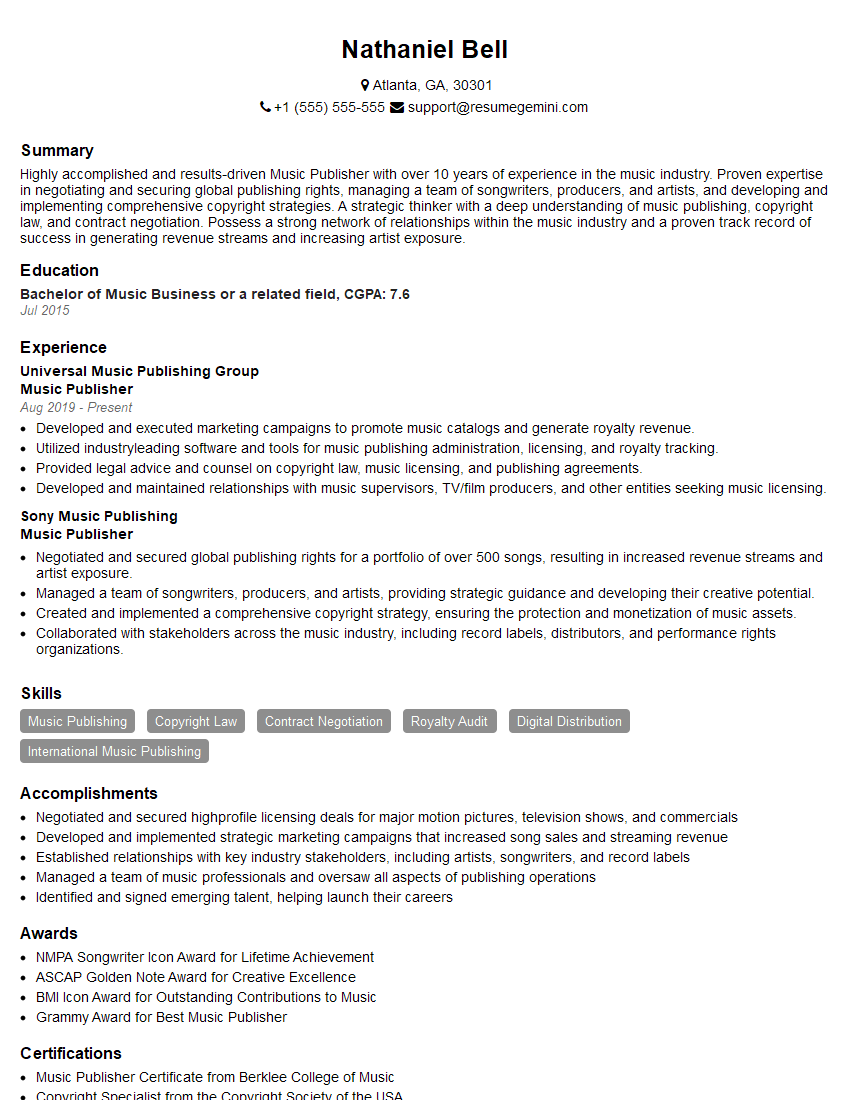

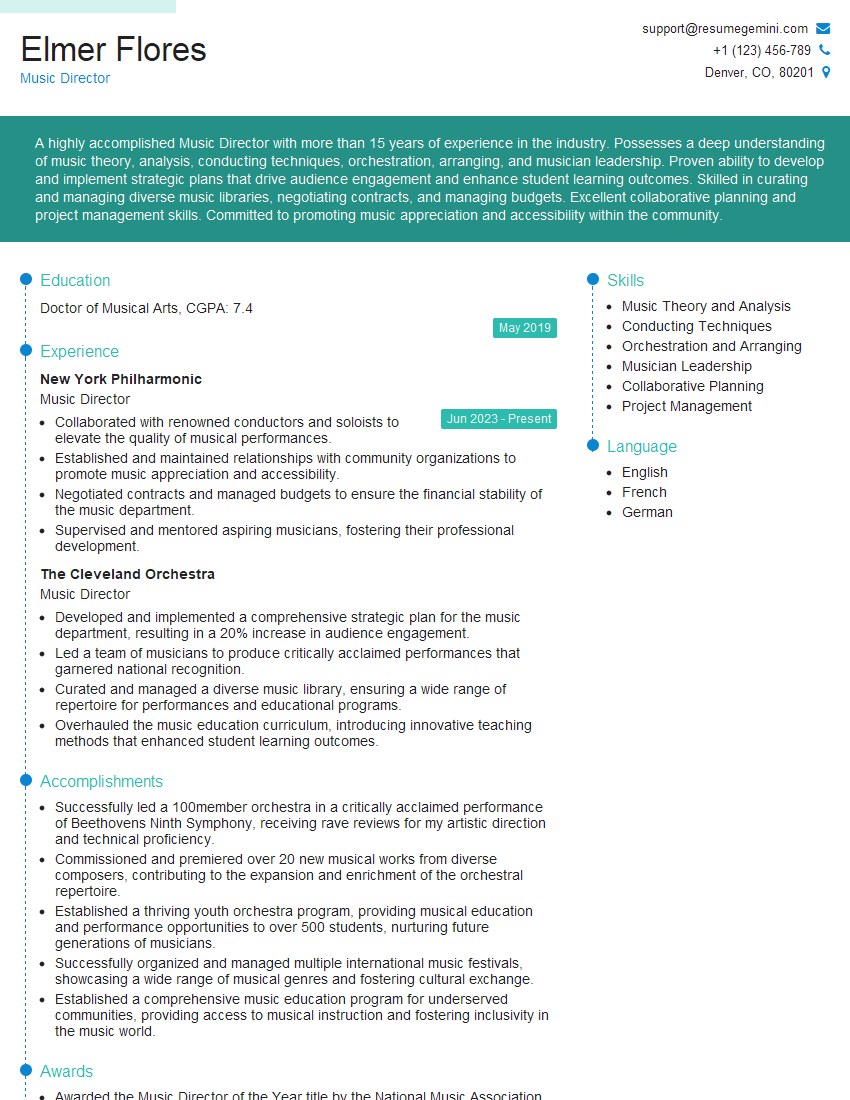

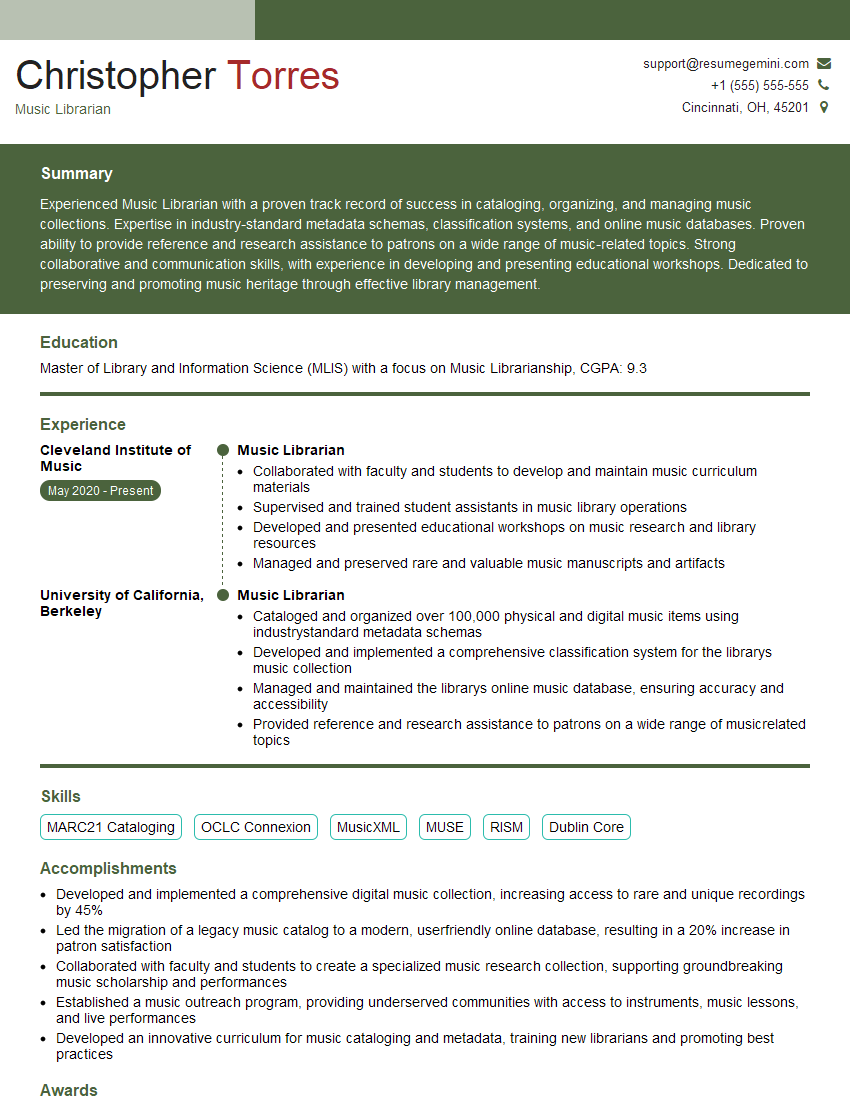

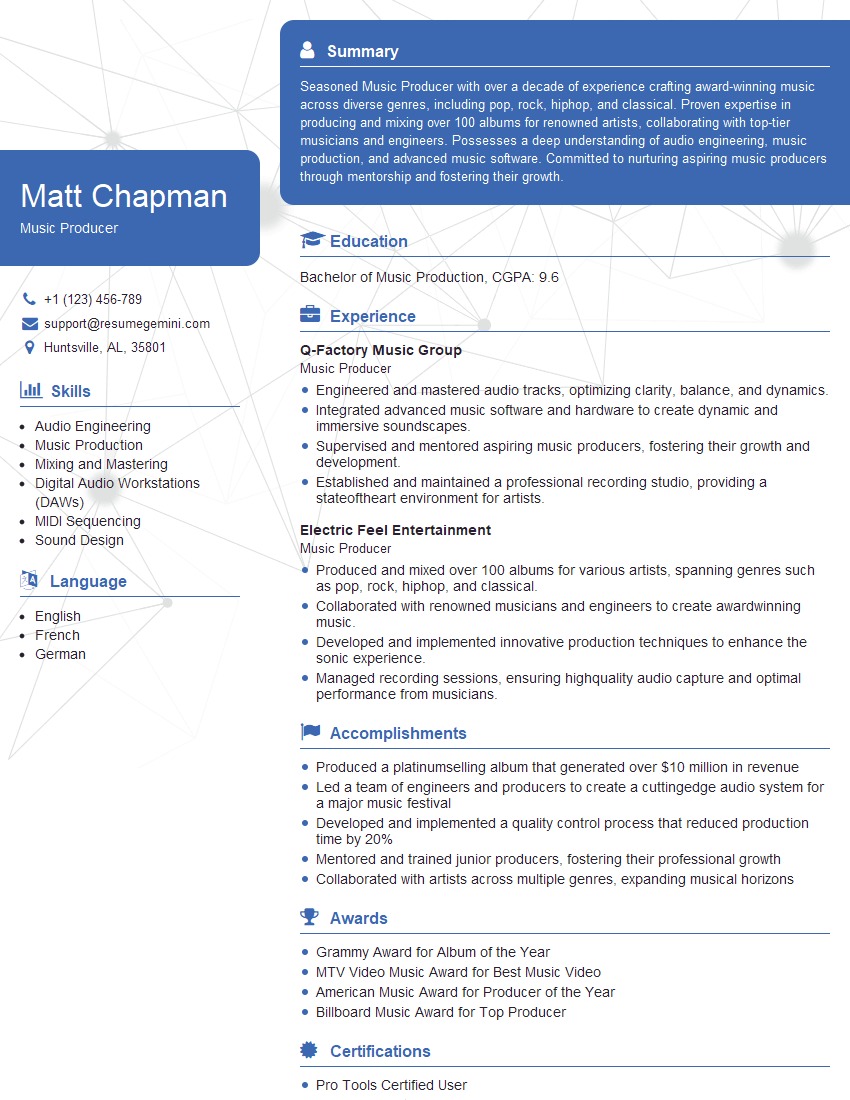

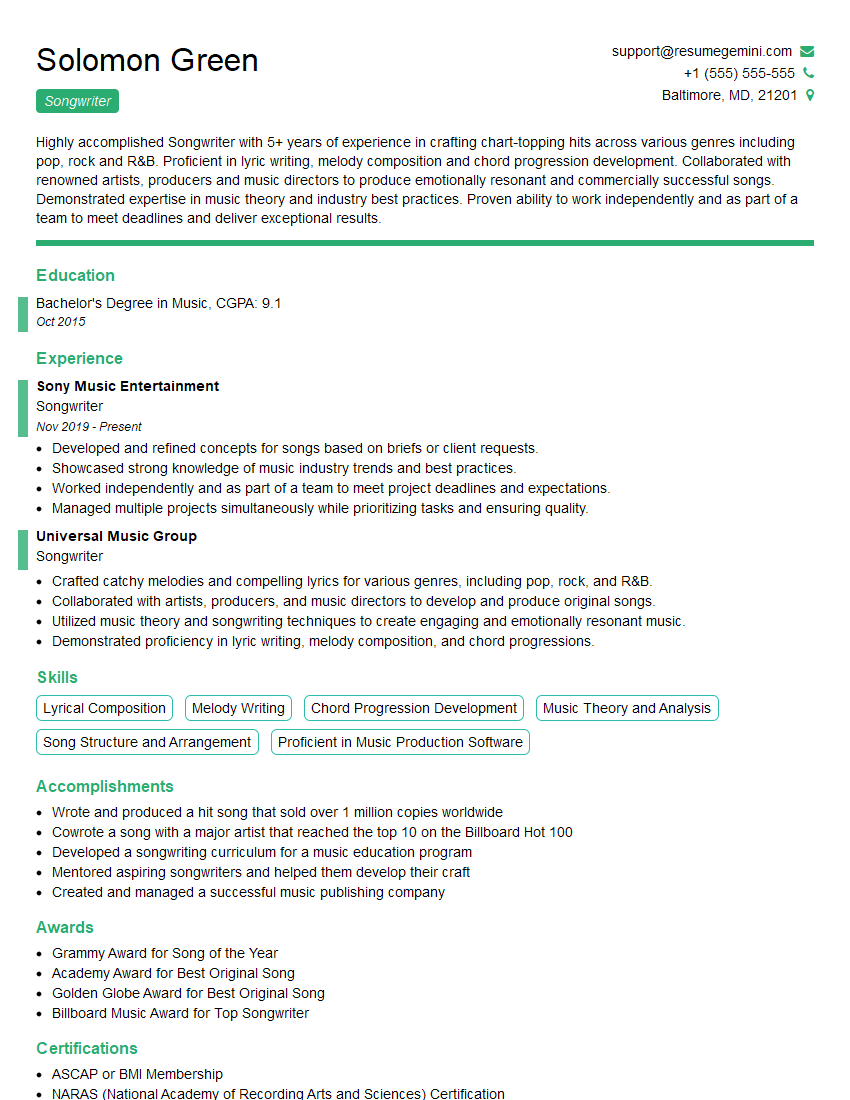

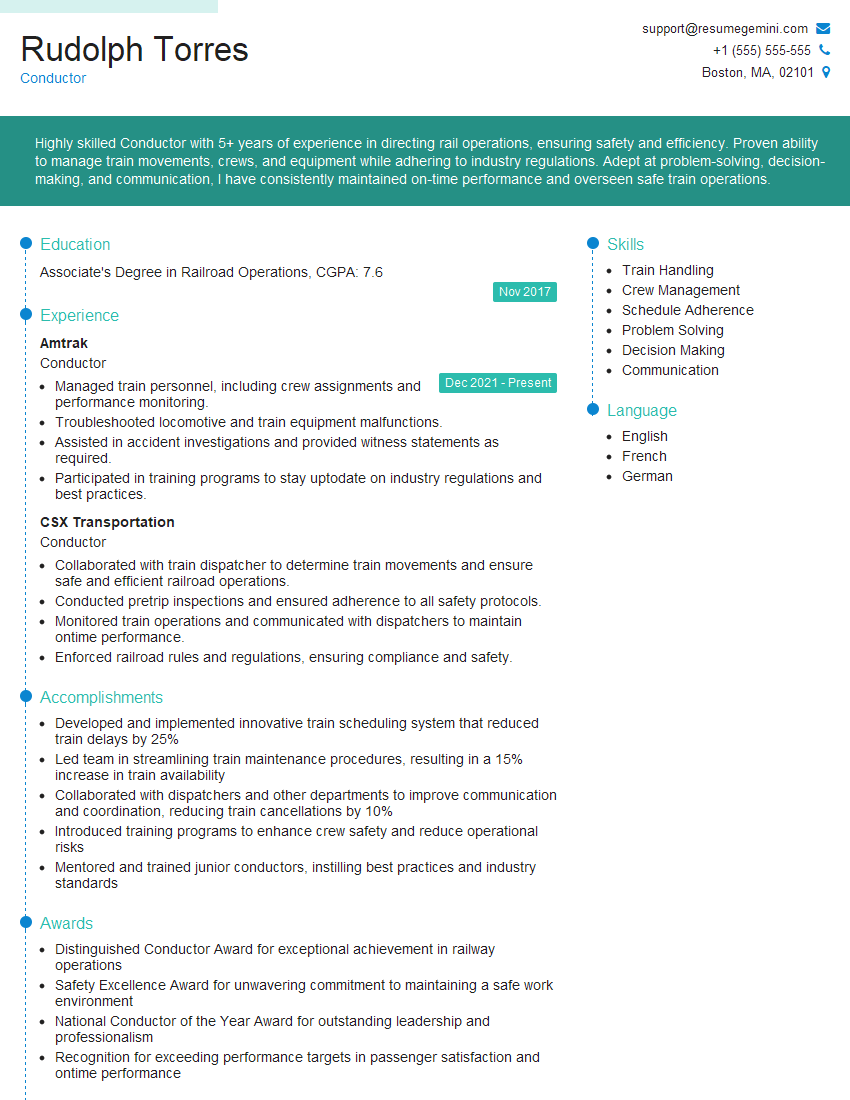

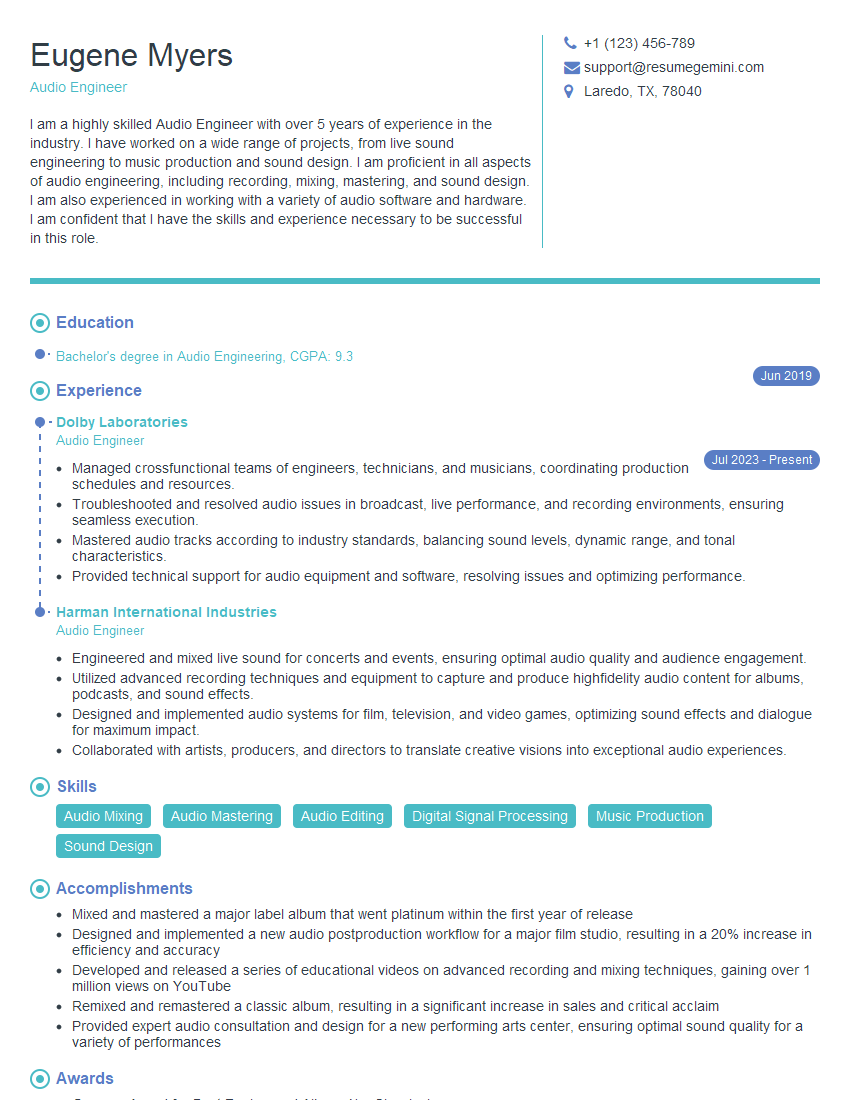

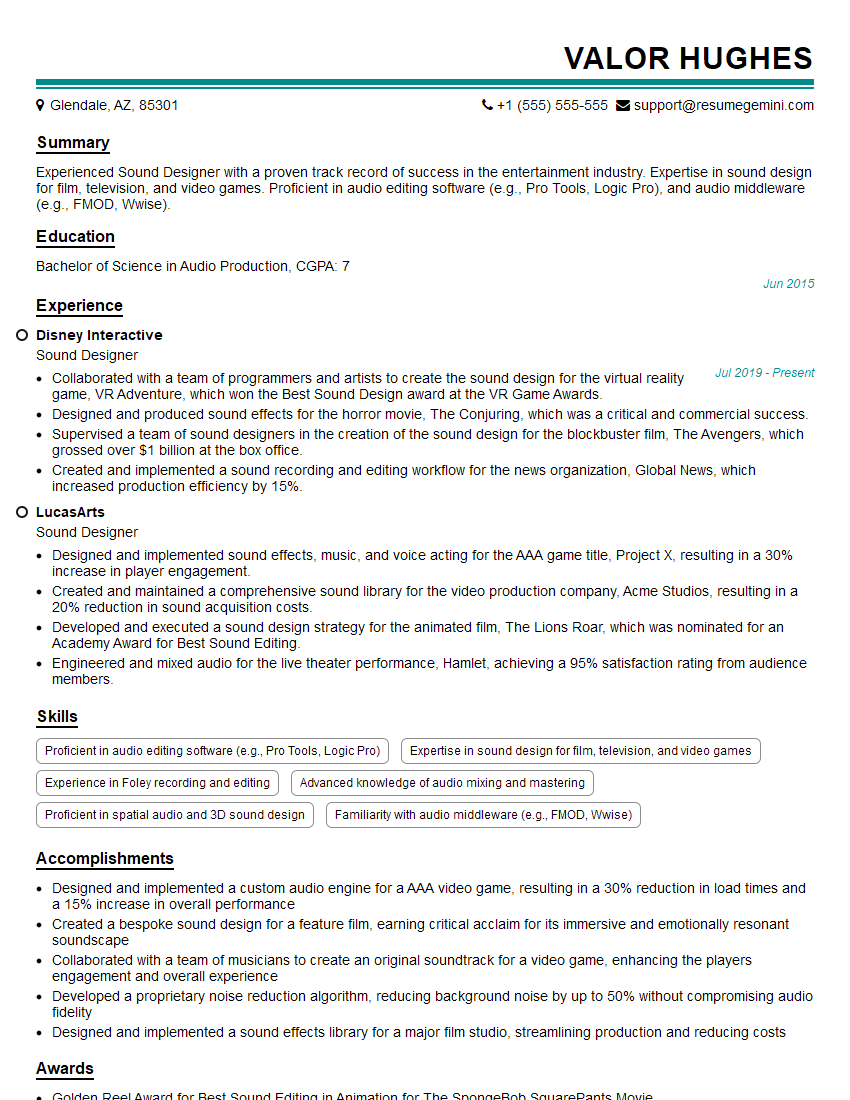

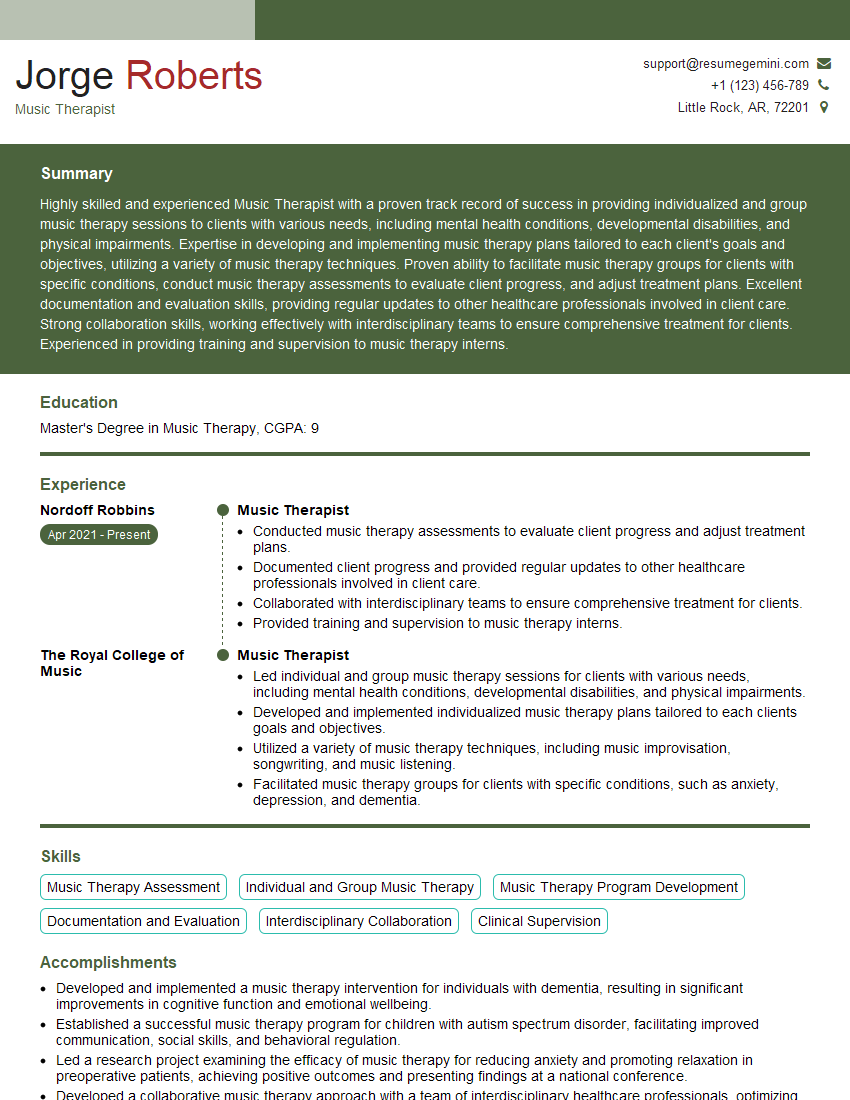

Mastering proficiency in music theory and rhythm is crucial for career advancement in various musical fields, from composition and performance to music education and analysis. A strong understanding of these core concepts significantly enhances your capabilities and marketability. To maximize your job prospects, it’s essential to create an ATS-friendly resume that highlights your skills and experience effectively. ResumeGemini is a trusted resource that can help you build a professional and impactful resume tailored to your specific needs. We offer examples of resumes tailored to showcasing Proficiency in Music Theory and Rhythm to help you get started. Take the next step towards your dream career today!

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

Hello,

We found issues with your domain’s email setup that may be sending your messages to spam or blocking them completely. InboxShield Mini shows you how to fix it in minutes — no tech skills required.

Scan your domain now for details: https://inboxshield-mini.com/

— Adam @ InboxShield Mini

Reply STOP to unsubscribe

Hi, are you owner of interviewgemini.com? What if I told you I could help you find extra time in your schedule, reconnect with leads you didn’t even realize you missed, and bring in more “I want to work with you” conversations, without increasing your ad spend or hiring a full-time employee?

All with a flexible, budget-friendly service that could easily pay for itself. Sounds good?

Would it be nice to jump on a quick 10-minute call so I can show you exactly how we make this work?

Best,

Hapei

Marketing Director

Hey, I know you’re the owner of interviewgemini.com. I’ll be quick.

Fundraising for your business is tough and time-consuming. We make it easier by guaranteeing two private investor meetings each month, for six months. No demos, no pitch events – just direct introductions to active investors matched to your startup.

If youR17;re raising, this could help you build real momentum. Want me to send more info?

Hi, I represent an SEO company that specialises in getting you AI citations and higher rankings on Google. I’d like to offer you a 100% free SEO audit for your website. Would you be interested?

Hi, I represent an SEO company that specialises in getting you AI citations and higher rankings on Google. I’d like to offer you a 100% free SEO audit for your website. Would you be interested?

good