Unlock your full potential by mastering the most common Harmony and Composition interview questions. This blog offers a deep dive into the critical topics, ensuring you’re not only prepared to answer but to excel. With these insights, you’ll approach your interview with clarity and confidence.

Questions Asked in Harmony and Composition Interview

Q 1. Explain the difference between diatonic and chromatic harmony.

Diatonic and chromatic harmony represent two fundamental approaches to constructing chords and progressions within a tonal system. Diatonic harmony uses notes exclusively from the diatonic scale (the familiar ‘do-re-mi’ scale), creating a sense of stability and consonance. Chromatic harmony, conversely, introduces notes from outside the diatonic scale – the chromatic scale (all the notes, including sharps and flats) – adding color, tension, and sometimes dissonance. Think of it like this: diatonic harmony is like a comfortable, familiar chair; chromatic harmony is like a surprising, exciting rollercoaster.

For example, in the key of C major, a diatonic chord progression might be C-G-Am-F. These chords all contain only notes found in the C major scale. A chromatic progression might incorporate a diminished chord, like B-diminished, which contains notes (B, D, F) not found in the C major scale, creating a sense of harmonic tension that resolves.

Q 2. Describe the function of secondary dominants in tonal music.

Secondary dominants are chords that function as dominant chords (V chords), but not to the tonic (I chord) of the key. Instead, they prepare a chord other than the tonic. They create a powerful harmonic pull towards their resolution. Imagine them as temporary detours on a musical journey, leading to a satisfying arrival at a different destination than initially expected. They add harmonic color and create a sense of anticipation.

For instance, in C major, the dominant chord (G major) leads to C major (the tonic). A secondary dominant to G major would be D7, which strongly pulls to G major, which then leads to C major. This creates a richer and more interesting harmonic progression than a simple I-V-I cadence.

Cmaj - D7 - Gmaj - CmajQ 3. How do you use voice leading to create smooth transitions between chords?

Voice leading is the art of smoothly connecting the notes of consecutive chords. The goal is to minimize leaps and maximize stepwise motion (movement of a single note interval) for a seamless flow between chords. Effective voice leading creates a feeling of fluidity and avoids jarring transitions. Think of it as gracefully guiding individual musical voices through a conversation, rather than abruptly interrupting them.

Consider a transition from a C major chord (C-E-G) to an F major chord (F-A-C). Good voice leading might involve moving the C to the C (common tone), the E to the F (stepwise motion), and the G to the A (stepwise motion). Poor voice leading might involve large leaps between notes, creating a disruptive sound.

Q 4. Explain the concept of chord inversions and their effect on voicing.

Chord inversions refer to rearranging the order of notes within a chord without changing the root. This affects the voicing – the specific arrangement of notes in the chord – giving each inversion a unique character and bass note. Different inversions emphasize different notes and create diverse harmonic colors. The original arrangement, with the root in the bass, is called root position. The first inversion has the third in the bass, and the second inversion has the fifth in the bass.

For example, a C major chord (C-E-G) in root position has C in the bass. The first inversion (E-G-C) has E in the bass, and the second inversion (G-C-E) has G in the bass. These inversions change the overall sound and feel of the chord, adding variety and interest to a composition.

Q 5. What are common techniques for creating tension and release in a musical composition?

Creating tension and release is fundamental to musical expression. It’s like building anticipation for a satisfying payoff. Techniques for building tension include using dissonant chords (chords that sound unstable), chromaticism, suspensions (holding a note from a previous chord), and rhythmic complexity. Release is achieved through resolving the tension with consonant chords (chords that sound stable), simple rhythmic patterns, and a return to the tonic chord (home chord).

For example, using a dominant 7th chord before a tonic chord builds tension that is resolved by the tonic. Similarly, a sudden shift to a minor key can create tension which can be released by returning to the major key. The interplay between tension and release is vital for emotional impact.

Q 6. Describe different types of cadences and their emotional impact.

Cadences are harmonic progressions that mark the end of a musical phrase or section. Different types of cadences evoke different emotional responses. An authentic cadence (V-I) is the most common and often creates a feeling of finality and resolution. A half cadence (V), ending on the dominant chord, leaves the listener feeling a sense of incompleteness and expectation. A deceptive cadence (V-VI) subverts expectations and creates surprise, often leading to a sense of intrigue or unease.

The perfect authentic cadence (V-I) is like the satisfying conclusion of a story. The half cadence (V) is like a cliffhanger, leaving you wanting more. The deceptive cadence (V-VI) is like a plot twist – unexpected and engaging.

Q 7. Explain how to analyze a piece of music for its harmonic structure.

Analyzing a piece’s harmonic structure involves identifying the chords, their functions, and how they relate to one another. This often includes identifying the key, analyzing chord progressions, and recognizing cadences. It’s a bit like detective work, uncovering the underlying blueprint of the composition.

Start by identifying the key. Then, analyze the progression, determining the function of each chord (tonic, dominant, subdominant, etc.). Pay close attention to the relationships between chords (e.g., diatonic or chromatic relationships). Note the use of secondary dominants, inversions, and other harmonic devices. Finally, identify and classify the cadences to understand how the piece builds and resolves its harmonic tension. Software like Sibelius or Finale can aid in this process by automatically charting harmonic analysis.

Q 8. Discuss the use of modulation in expanding harmonic vocabulary.

Modulation, the process of changing from one key to another, is a cornerstone of expanding harmonic vocabulary. It allows composers to move beyond the limitations of a single key, creating richer and more varied harmonic landscapes. Think of it like changing the ‘color’ of your musical palette. A piece solely in C major might feel monotonous, but by modulating to, say, G major or A minor, we introduce new harmonies and emotional textures.

The effectiveness of modulation depends on several factors: the relationship between the keys (closely related keys like those sharing many notes create a smoother transition, while distant keys create more dramatic shifts), the context of the modulation (a sudden modulation can be jarring, while a carefully prepared modulation can be seamless), and the composer’s intent (modulation can serve to create surprise, contrast, or build towards a climax).

For example, a classical composer might modulate to the dominant key (V) to create tension before resolving back to the tonic (I), a common practice. A more contemporary composer might use more adventurous and unexpected modulations to explore unusual harmonic territories.

Q 9. How do you approach composing for different instrumental combinations?

Composing for different instrumental combinations requires a deep understanding of each instrument’s timbre, range, and technical capabilities. It’s not simply a matter of transcribing a piece written for one ensemble to another; it demands a reimagining of the musical texture and harmonic possibilities.

For instance, composing for a string quartet demands a different approach than composing for a brass quintet. Strings excel in legato lines and subtle dynamic shifts, whereas brass instruments are known for their powerful, resonant tones and assertive articulation. My approach involves:

- Analyzing instrumental ranges and timbres: I carefully consider each instrument’s unique sonic characteristics and how they interact with each other.

- Exploiting individual instrument strengths: I write passages that showcase the strengths of each instrument. For instance, I might assign a soaring melody to the oboe or a powerful rhythmic figure to the tuba.

- Balancing textures: I strive for a well-balanced texture, ensuring that no single instrument overshadows the others. I avoid writing passages that are overly dense or sparse.

- Considering technical limitations: I am mindful of the technical limitations of each instrument and write parts that are playable and expressive within those limitations.

Q 10. What are some common approaches to creating thematic development?

Thematic development is the process of transforming a musical idea—a theme—throughout a composition. It’s what keeps a piece engaging and prevents it from becoming monotonous. Think of it like a sculptor refining a piece of clay, gradually revealing its beauty through careful shaping and refinement.

Common approaches include:

- Sequence: Repeating a musical phrase at a different pitch level. This creates a sense of forward momentum.

- Fragmentation: Breaking a theme into smaller parts and rearranging or combining these fragments in new ways. This adds complexity and intrigue.

- Imitation: Presenting the theme in a different voice or instrument, perhaps with slight variations in rhythm or ornamentation. This creates a sense of dialogue between different musical lines.

- Variation: Altering the theme by changing its rhythm, melody, harmony, or texture. This adds contrast and keeps the listener engaged.

- Development through modulation: Exploring different harmonic areas through modulation can reveal new facets of a theme.

For instance, a simple melody might be developed through sequence, then fragmented and presented in counterpoint with another melody, before being transformed through variation in a different key.

Q 11. Explain the concept of counterpoint and its role in composition.

Counterpoint is the art of combining independent melodic lines in a way that creates a satisfying and interesting musical texture. It’s like weaving a tapestry, where each thread (melody) is distinct but contributes to the overall design (composition). The lines can be independent, intertwining, or harmonically related. Good counterpoint is characterized by clear melodic lines that are harmonically compatible and maintain their individual character.

In composition, counterpoint plays a crucial role in:

- Creating harmonic richness: The interplay between independent lines generates a richer harmonic texture than a single melody with accompaniment.

- Adding complexity and interest: Well-crafted counterpoint keeps the listener engaged by providing multiple layers of musical interest.

- Developing thematic material: Counterpoint can be used to develop a theme by presenting it in different voices or by combining it with other themes.

- Creating a sense of movement: The interplay of independent lines generates a sense of forward momentum and rhythmic vitality.

Examples of counterpoint are abundant in Baroque music, particularly in the works of Bach and Handel. Their fugues, for instance, are masterclasses in counterpoint, showcasing intricate melodic interweavings.

Q 12. How do you use rhythmic variation to enhance harmonic interest?

Rhythmic variation is a powerful tool for enhancing harmonic interest. By changing the rhythmic patterns associated with a particular harmony, you can create a sense of surprise, anticipation, or rhythmic drive. It adds a dynamic dimension to the harmonic progression, preventing it from sounding static or predictable.

For instance, a simple I-IV-V-I progression in 4/4 time might become more interesting by using syncopation in the IV chord, introducing a dotted rhythm in the V chord, and employing a hemiola (a rhythmic pattern where a 3/4 feel is superimposed on a 4/4 meter) in the I chord. This shifts the rhythmic emphasis and creates a more dynamic and exciting harmonic journey.

Think of it like adding a dash of spice to a dish – a subtle rhythmic change can significantly heighten the impact of the harmonic flavors.

Q 13. Describe your approach to composing for a specific emotional effect.

Composing for a specific emotional effect involves understanding the relationship between music and emotion. This involves choosing appropriate harmonies, melodies, rhythms, dynamics, and instrumentation to evoke the desired feeling. It’s akin to painting a picture with sound.

My approach involves:

- Harmony: Major keys often convey feelings of joy, happiness, and triumph, while minor keys are commonly associated with sadness, melancholy, and drama. Dissonance can be used to create tension and anxiety, while consonance can offer resolution and peace.

- Melody: Ascending melodies can feel uplifting and hopeful, while descending melodies can be melancholic or sorrowful. The contour and intervallic structure of a melody significantly influence its emotional impact.

- Rhythm: Fast tempos tend to convey excitement and energy, while slow tempos can create a sense of calmness or solemnity. Rhythmic irregularities can create a sense of unease or tension.

- Dynamics: Sudden changes in volume (dynamics) can amplify emotional impact. A crescendo can build tension, while a diminuendo can suggest a fading emotion.

- Instrumentation: Different instruments have different timbres that evoke different emotions. Strings might convey elegance and sorrow, while brass instruments might convey power and grandeur.

For example, to evoke feelings of serene tranquility, I might use a slow tempo, simple major key harmonies, soft dynamics, and a flute melody. To convey intense drama, I might employ complex dissonances, a fast tempo, powerful dynamics, and a full orchestral sound.

Q 14. How do you resolve dissonance in your compositions?

The resolution of dissonance is a fundamental aspect of harmony. Dissonance, by definition, is a combination of notes that sounds unstable or unpleasant, while consonance sounds stable and pleasing. The resolution of dissonance involves moving from an unstable harmony to a stable one, creating a sense of satisfaction and closure. This is like releasing tension after a build-up.

Common techniques for resolving dissonance include:

- Moving dissonant notes to consonant intervals: Dissonant intervals (like major sevenths or augmented seconds) are often resolved by moving the dissonant note to a consonant interval (like a perfect fifth or octave) with the neighboring note.

- Using passing tones and neighboring tones: Non-chord tones, such as passing tones and neighboring tones, are used to create a smooth transition between chords and to resolve dissonances naturally.

- Leading tones: The leading tone (the seventh degree of a diatonic scale) typically resolves upwards to the tonic (the first degree of the scale), creating a powerful sense of resolution.

- Delayed resolution: Sometimes, delaying the resolution of dissonance can create additional tension and anticipation before the eventual resolution.

The choice of resolution method depends heavily on the style, context, and the desired emotional effect. A sudden resolution might create a sense of relief, while a gradual resolution might evoke a feeling of gradual release of tension.

Q 15. Explain your understanding of different harmonic periods (e.g., Baroque, Classical, Romantic).

Harmonic periods reflect significant shifts in musical aesthetics and compositional practices. Each period showcases unique approaches to harmony, tonality, and dissonance resolution.

Baroque (roughly 1600-1750): Characterized by a strong sense of basso continuo (a continuous bass line supporting the harmony), relatively simple chord progressions often based on figured bass, and a focus on counterpoint. Major and minor tonality was firmly established, but complex chromaticism was sparingly used. Think of the rich harmonies in Bach’s fugues – they often use a limited number of chords yet create immense harmonic depth through counterpoint and careful voice leading.

Classical (roughly 1730-1820): The Classical period saw a move towards greater clarity and simplicity in harmony. Homophonic texture (melody with accompaniment) became more dominant. Diatonic harmony (using notes within the key) reigned supreme, with clear cadences (harmonic resolutions) creating a sense of structure and closure. Haydn’s symphonies are excellent examples of this period’s balanced and elegant harmony.

Romantic (roughly 1820-1900): The Romantic period embraced chromaticism (notes outside the key) and expanded harmonic vocabulary extensively. Greater use of dissonance and delayed resolution created dramatic tension and emotional expressiveness. Composers explored extended harmonies, altered chords, and even hinted at atonality. Think of the lush, complex harmonies found in Wagner’s operas or the dramatic chord progressions in Liszt’s piano works. The emotional impact of the music was strongly tied to the harmonic language used.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. What are some common harmonic progressions and their characteristics?

Common harmonic progressions are like building blocks in musical composition. They form the foundation upon which more complex structures are built.

I-IV-V-I (Tonic-Subdominant-Dominant-Tonic): This progression, found in countless pieces across various genres, creates a satisfying sense of resolution. The I chord (tonic) provides stability, the IV (subdominant) introduces a sense of expectation, the V (dominant) creates tension, and the return to I resolves that tension. It’s essentially a musical “story” of tension and release.

Example: C-F-G-Cii-V-I: This progression, highly characteristic of jazz and popular music, is also incredibly effective. The ii chord (supertonic) adds a certain color before the dominant V creates tension and the tonic I resolves it.

Example: Dm-G-Cvi-IV-I-V: This progression can add a touch of melancholy or wistfulness. The vi chord (submediant) creates a softer, less direct approach to the tonic than the ii-V-I progression.

Example: Am-F-C-GI-vi-IV-V: This progression adds a bit of a twist to the typical I-IV-V-I, using the vi chord to add color and some harmonic interest before the dominant V.

Example: C-Am-F-G

These are just a few examples; countless variations and combinations are possible. The characteristic of each progression depends largely on the context and the composer’s intent.

Q 17. Discuss your experience with different compositional techniques (e.g., serialism, atonality).

My compositional experience encompasses both traditional tonal harmony and more experimental approaches like serialism and atonality.

Serialism: This technique involves composing with a pre-determined series of notes (a tone row) that is manipulated through various transformations (inversion, retrograde, etc.) to govern melody, harmony, and rhythm. It aims for a systematic and non-tonal approach to composition. While demanding technically, it allows for the creation of complex and unique harmonic landscapes.

Atonality: Atonal music lacks a tonal center or key. It relies on the juxtaposition of dissonant chords and intervals, creating a sense of ambiguity and freedom from traditional harmonic constraints. It necessitates careful consideration of timbre, rhythm, and form to maintain coherence. Schoenberg’s work is a cornerstone of atonal music.

My approach is to adapt the compositional technique to the musical narrative I want to convey. Sometimes a traditional tonal approach is the most effective, while other times, the freedom of atonal or serial techniques allows for a more appropriate expression.

Q 18. How do you incorporate melodic ideas into your harmonic structures?

Melodic ideas and harmonic structures are deeply intertwined; they inform and shape each other. The melody often dictates the harmonic progression, while the harmony provides a framework for the melodic contour. Think of it as a conversation.

My process typically involves sketching melodic fragments first. Once I have a sense of the melodic direction, I begin to explore the underlying harmony. I might choose chords that emphasize certain melodic notes, create tension and release points, or reinforce the melodic contour. Sometimes the melody might need adjustments based on the harmonic framework I’ve created. It’s an iterative process—a dance between melody and harmony—until they achieve a satisfying balance.

For example, a rising melodic line might be supported by a progression of ascending chords, whereas a descending line might be accompanied by resolving harmonies.

Q 19. Explain the role of harmony in creating musical form.

Harmony plays a vital role in shaping musical form. It provides a structural framework that guides the listener through the piece.

Changes in harmony often mark transitions between sections (e.g., moving from a tonic-based section to a dominant-based section signals a shift in mood or intensity). Harmonic repetition reinforces themes and sections, while harmonic contrast distinguishes different parts of a piece. The use of cadence (a harmonic progression that implies resolution or closure) signals the end of phrases, sections, or even the entire composition.

For instance, in a sonata form, the tonic harmony typically dominates the exposition and recapitulation, while the dominant harmony prevails in the development section. This creates a clear sense of structure and progression for the listener.

Q 20. Describe your process for composing a piece of music, from concept to completion.

My compositional process is iterative and often unfolds organically. It typically involves these steps:

Concept & Inspiration: This could be a specific emotion, image, story, or even a pre-existing melodic or rhythmic idea. I’ll brainstorm and explore various options until a compelling concept emerges.

Sketching: I begin sketching melodies, harmonies, and rhythms. At this stage, it’s more about experimentation and exploring possibilities than perfection.

Development: I start to flesh out the ideas from the sketching phase, working on melodic development, harmonic progressions, and overall form. This usually involves a lot of trial and error, rewriting, and refinement.

Instrumentation & Orchestration: I decide which instruments or voices will best convey my musical ideas. I then consider the timbre, texture, and dynamics of each instrument or voice within the overall context of the piece.

Revision & Refinement: This is a crucial stage, involving multiple rounds of listening, critical evaluation, and adjustment. I often seek feedback from colleagues or mentors to gain an outside perspective.

Finalization & Production: Once satisfied with the piece, I finalize the score and, if necessary, produce a recording.

Throughout the entire process, I maintain a balance between intuition and critical analysis. I allow for spontaneity and creativity while ensuring a strong structural foundation.

Q 21. How do you handle creative blocks or challenges in the compositional process?

Creative blocks are a common challenge for composers. When I encounter them, I use a variety of strategies:

Step Away: Sometimes, the best solution is to simply step away from the project for a while. This allows for fresh perspective and reduces pressure.

Explore Different Approaches: I might try experimenting with different instruments, styles, or harmonic techniques to break free from a rut.

Seek Inspiration: Listening to music, visiting museums, spending time in nature, or engaging in other creative activities can spark new ideas.

Work on a Different Project: Sometimes, focusing on a different piece can help unlock creative energy that can then be applied to the challenging piece.

Collaborate: Discussing my challenges with colleagues or mentors can provide valuable feedback and fresh insights.

The key is to remain persistent and adaptable. Creative blocks are temporary roadblocks, not insurmountable obstacles.

Q 22. How familiar are you with music notation software (e.g., Sibelius, Finale)?

I’m highly proficient in music notation software. My primary software is Sibelius, which I’ve used extensively for over ten years, from sketching initial ideas to creating polished scores for orchestra, chamber ensembles, and solo instruments. I’m also familiar with Finale and have used it for specific projects requiring its unique features, such as its advanced engraving capabilities for certain types of notation. My expertise extends beyond basic input; I’m adept at using advanced features like expression maps, customizing templates, and creating highly detailed scores with sophisticated layouts. I use these tools not just to transcribe my compositions but also to experiment with different orchestrations and explore harmonic possibilities.

Q 23. What are some of your favorite composers and why?

My musical tastes are quite broad, but some composers consistently inspire me. J.S. Bach, for his unparalleled mastery of counterpoint and harmonic ingenuity, consistently challenges and rewards study. His ability to create immense complexity while maintaining an almost effortless elegance is a constant source of inspiration. Similarly, I find myself returning to the works of Béla Bartók. His innovative use of folk melodies, his rhythmic vitality, and his bold harmonic language are incredibly influential. Finally, Debussy’s impressionistic style, with its focus on color and atmosphere, continues to fascinate. The way he uses harmony to evoke specific moods and sensory experiences is truly remarkable. Each of these composers represents a different approach to composition, but they all share a profound understanding of musical structure and a dedication to pushing the boundaries of the art form.

Q 24. Describe a piece of music you’ve composed and its harmonic structure.

One of my recent compositions is a string quartet titled ‘Nocturne.’ The piece explores the emotional landscape of quiet contemplation. Harmonic structure is based around a central motif, a minor chord progression that gradually evolves throughout the piece. The opening movement establishes this motif in a relatively simple form, using primarily diatonic harmony. As the piece progresses, chromaticism is gradually introduced, creating a sense of growing tension and unease. In the second movement, there is a more freely structured passage using modal interchange, moving between different keys related to the tonic minor, creating a sense of ambiguity and dreamlike quality. The final movement resolves back to the central motif, but this time it’s enriched by a richer texture and more complex harmonies, concluding with a sense of quiet acceptance.

The harmonic structure could be loosely described as a modified sonata form, where the main themes are built from various transformations of the central motif. The piece extensively uses suspensions and appoggiaturas to enhance the expressive quality and add to the harmonic richness.

Q 25. Explain your understanding of different musical textures (e.g., monophonic, polyphonic).

Musical texture refers to the way different melodic and rhythmic elements interact within a piece.

- Monophonic texture features a single melodic line, without accompaniment. Think of a Gregorian chant or a simple folk melody.

- Polyphonic texture involves two or more independent melodic lines sounding simultaneously. This is characteristic of much of Bach’s work, where multiple voices intertwine in complex yet organized counterpoint.

- Homophonic texture is characterized by a single melody accompanied by chords. Most popular music falls into this category, where the melody is the primary focus and the harmony provides support.

- Heterophonic texture is where a single melody is performed simultaneously with slight variations in the different parts. This is common in some folk music traditions.

Q 26. How do you balance complexity and accessibility in your compositions?

Balancing complexity and accessibility is a constant challenge in composition. It’s about finding the sweet spot between innovation and listenability. I approach this by layering complexity. The underlying harmonic structure might be intricate, employing sophisticated techniques like extended chords or altered dominants. However, the melodic lines themselves can be relatively simple and memorable. This allows listeners to appreciate the underlying complexity without feeling overwhelmed. I also carefully consider the overall form and structure. A well-defined structure helps to guide the listener through even the most complex passages. Finally, the use of contrast is essential. Alternating between sections of high complexity and moments of simplicity can maintain listener engagement while allowing for both depth and accessibility. It’s a delicate dance, but the reward is a piece that is both intellectually stimulating and emotionally engaging.

Q 27. How do you incorporate your understanding of harmony and composition into other aspects of music production?

My understanding of harmony and composition informs virtually every aspect of my music production. In arranging, harmonic knowledge helps in creating effective voicings for chords and building interesting instrumental parts that complement the melody. When producing, harmonic considerations guide my choices of sounds, effects, and mixing techniques. For example, I might choose specific synth sounds to emphasize particular harmonic intervals, and I would use EQ and compression to enhance the clarity of certain harmonic elements within the mix. Essentially, harmony and composition are the foundational pillars upon which I build every musical element. This understanding allows for a more cohesive and well-integrated approach to creating compelling music.

Q 28. Explain your familiarity with various musical styles and genres.

My familiarity with musical styles and genres is extensive. I’m comfortable working within classical traditions, from Baroque counterpoint to contemporary compositional techniques. I’m also well-versed in various popular genres, including jazz, rock, and electronic music. This diverse knowledge enables me to draw inspiration from different styles and to integrate them into my own compositional voice. Understanding the harmonic and compositional conventions of each genre is essential for creating convincing and authentic-sounding music within those styles. This breadth of knowledge allows me to create music that is both innovative and grounded in tradition, blending elements from disparate sources to create something new and unique.

Key Topics to Learn for Harmony and Composition Interview

- Fundamental Intervals and Chords: Understand the construction and function of major, minor, augmented, and diminished intervals and triads. Be prepared to discuss their inversions and applications within a musical context.

- Diatonic Harmony: Master the principles of diatonic harmony, including chord progressions, cadences, and modulation within a key. Practice analyzing and creating simple harmonic progressions.

- Chromatic Harmony: Explore the use of chromatic chords and alterations to create tension and release, enhancing harmonic richness and expressive possibilities. Be ready to discuss their effect on the overall tonality.

- Non-Functional Harmony: Familiarize yourself with approaches to harmony outside of traditional functional tonality, such as atonality, serialism, and other contemporary techniques. Be prepared to discuss their impact on musical style.

- Form and Structure: Understand common musical forms (e.g., sonata form, rondo, theme and variations) and how harmonic structure supports and reinforces these forms.

- Voice Leading: Master the principles of smooth and effective voice leading to create clear and logical harmonic progressions. Be prepared to analyze voice leading in existing compositions.

- Analysis Techniques: Develop skills in analyzing musical scores, identifying harmonic functions, and explaining the composer’s harmonic choices. Practice analyzing both simple and complex works.

- Practical Application: Be ready to discuss how you would apply your knowledge of harmony and composition in a practical setting, such as composing, arranging, or analyzing music.

- Problem-Solving: Practice identifying and resolving harmonic inconsistencies or ambiguities in musical examples. Develop strategies for approaching complex harmonic situations.

Next Steps

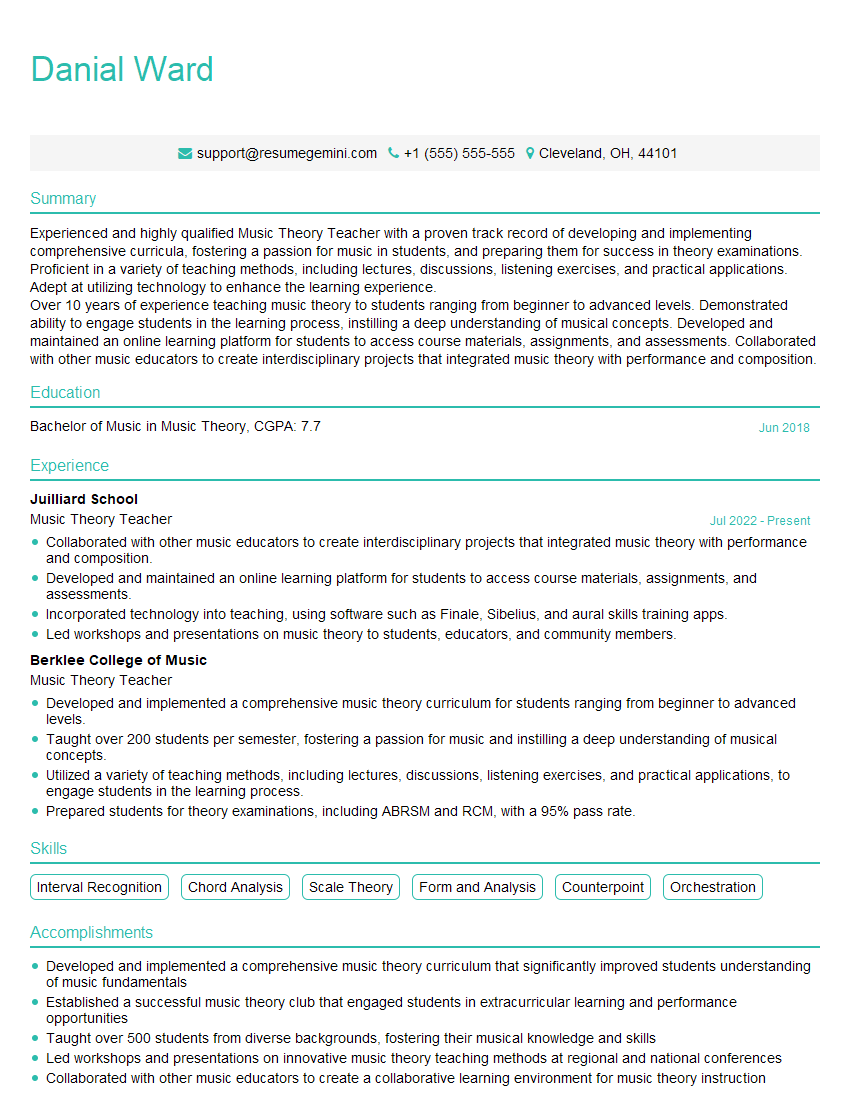

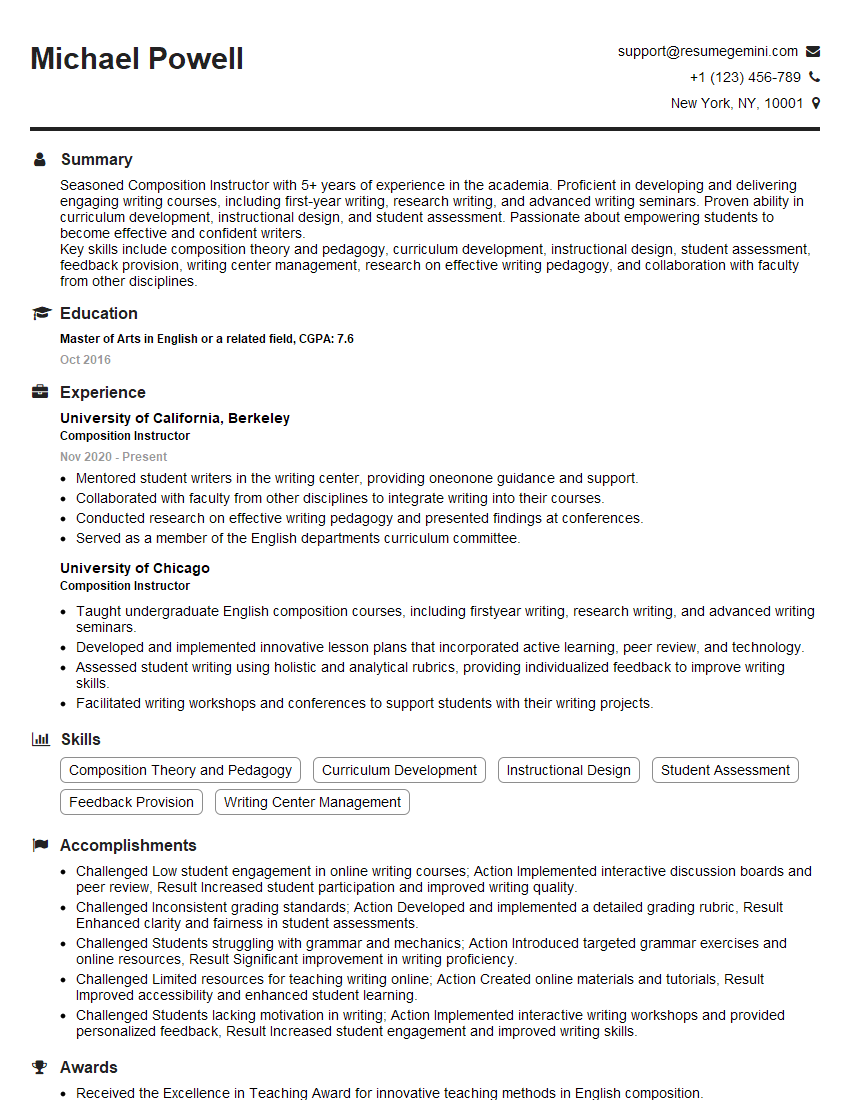

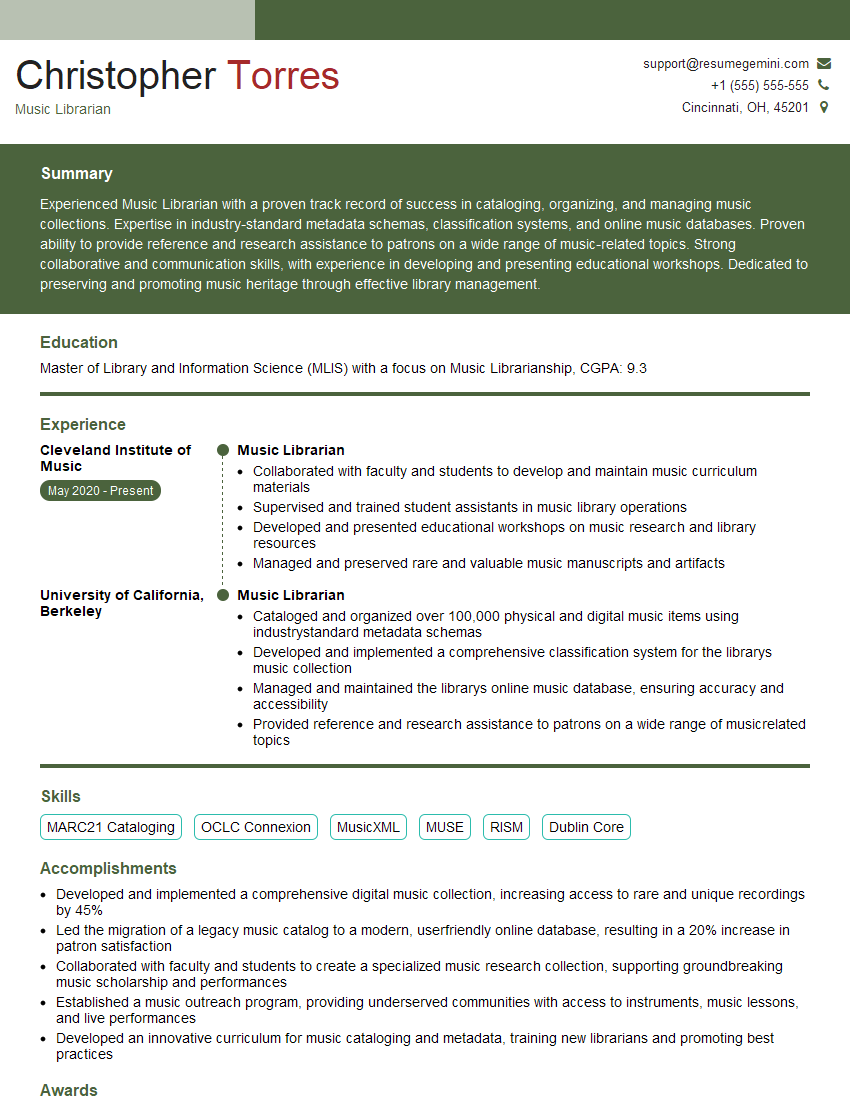

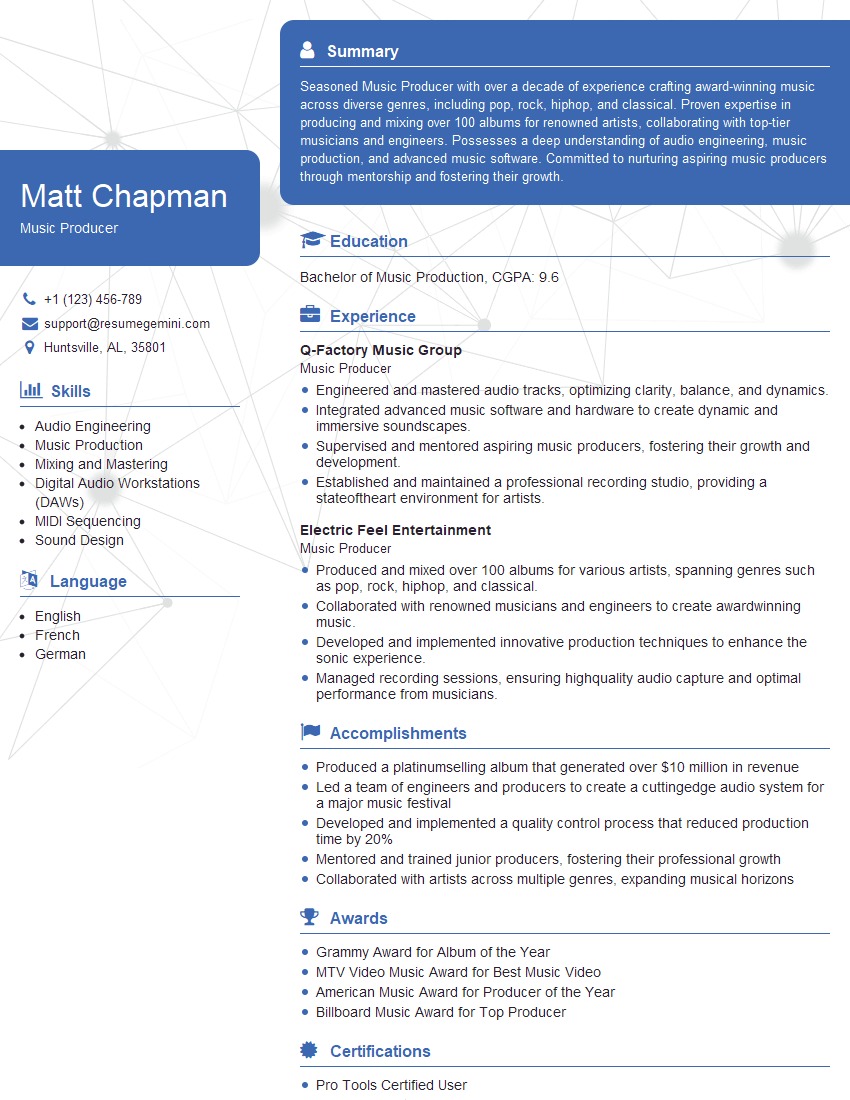

Mastering Harmony and Composition is crucial for career advancement in music-related fields. A strong understanding of these principles demonstrates a high level of musical proficiency and opens doors to diverse opportunities. To maximize your job prospects, create an ATS-friendly resume that effectively highlights your skills and experience. ResumeGemini is a trusted resource that can help you build a professional resume tailored to your specific needs. Examples of resumes tailored to Harmony and Composition are available to further enhance your application materials. Take the next step towards your dream career today!

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

Hello,

We found issues with your domain’s email setup that may be sending your messages to spam or blocking them completely. InboxShield Mini shows you how to fix it in minutes — no tech skills required.

Scan your domain now for details: https://inboxshield-mini.com/

— Adam @ InboxShield Mini

Reply STOP to unsubscribe

Hi, are you owner of interviewgemini.com? What if I told you I could help you find extra time in your schedule, reconnect with leads you didn’t even realize you missed, and bring in more “I want to work with you” conversations, without increasing your ad spend or hiring a full-time employee?

All with a flexible, budget-friendly service that could easily pay for itself. Sounds good?

Would it be nice to jump on a quick 10-minute call so I can show you exactly how we make this work?

Best,

Hapei

Marketing Director

Hey, I know you’re the owner of interviewgemini.com. I’ll be quick.

Fundraising for your business is tough and time-consuming. We make it easier by guaranteeing two private investor meetings each month, for six months. No demos, no pitch events – just direct introductions to active investors matched to your startup.

If youR17;re raising, this could help you build real momentum. Want me to send more info?

Hi, I represent an SEO company that specialises in getting you AI citations and higher rankings on Google. I’d like to offer you a 100% free SEO audit for your website. Would you be interested?

Hi, I represent an SEO company that specialises in getting you AI citations and higher rankings on Google. I’d like to offer you a 100% free SEO audit for your website. Would you be interested?

good